EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is another commentary from Atlanta-based human rights organization Justice Initiative, founded by Heather Gray. Here, she looks into the history of militarized police and its repressive roots at home and abroad.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

— Martin Luther King, Jr

Weapons of War On Our Streets: A Guide to the Militarization of America’s Police (Ammo.com)

Weapons of War On Our Streets: A Guide to the Militarization of America’s Police (Ammo.com)

Heather Gray

June 2, 2020

Justice Initiative

(Link to article)

Preface

Once again, with the recent tragic killing of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, young activists are wisely demonstrating throughout the United States demanding an end to this injustice, racism and white supremacy and of police violence.

Strange as it might seem, I began to learn more about the history of contemporary U.S. police violence while in the Philippines in 1989, which led me to better understand what we are experiencing regarding today’s scenario.

It is also likely that Donald Trump recently held a national call with governors of U.S. states to explore ways to take federal troops into the various states. The fact is, however, that the U.S. government is not allowed to send federal troops into the states at will, thanks to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 after the Civil War. “The purpose of the act… (was) to limit the powers of the Federal government in using its military personnel to enforce the state laws” (Posse Comitatus Act – Wikipedia).

Below is some history of the militarization of the U.S. police departments thanks to the early U.S. colonization of the Philippines and of the restraints of the federal government to militarize the states due to the Posse Comitatus Act. March 24, 2018 Atlanta “March for Our Lives in Atlanta” (Photo: Heather Gray)

March 24, 2018 Atlanta “March for Our Lives in Atlanta” (Photo: Heather Gray)

America’s Early Colonial History

In the 20th and 21rst centuries, U.S. policies around the world, both economically and militarily, have been questionable at best. U.S. violent international policies outside the Americas started with the Philippines in the beginning of the 20th century. These policies, more often incredibly violent, as mentioned, are coming back to haunt us. An example of this includes the U.S. international policy of “Low-Intensity Conflict” (LIC) related to the militarization of our domestic police forces.

After Philippine-American War (1899 to 1902), the U.S. launched LIC, at the beginning of the century in its Philippine colony, with the creation of the Philippine Constabulary. The Philippine Constabulary is, even today, a national police organization created principally to protect American and Filipino corporate and military elite interests. The legacy of this policy is that it now serves as a model for a militarized policing system in our 21rst century domestic American life.

I generally define the “elite” as neoconservative and neoliberal economic proponents along with their corporate capitalist supporters and colleagues.

The U.S. government and its elite tend to often try out policies internationally before introducing them into the U.S. and, as in the Philippines, the U.S. elite have always demonstrated their desire to control the American people. They certainly don’t want opposition to their policies or threats to their economic control, as we have consistently witnessed throughout the history of the U.S. Witness the FBI, the CIA, COINTELPRO, etc, and the assassination of many of our persuasive and profound leaders, such as Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and others.

Constraints on Militarization in the United States: Some History

I realize this is hard to believe, but often, the U.S. elite are constrained in implementing controlling policies in the U.S. domestic arena due to some laws that prevent this. They then will try to circumvent the restricting laws or attempt to overturn them altogether.

Not long after the end of the Civil War (in 1865), the United States government sent federal troops to the South to enforce the policies of the post-war Reconstruction period:

The Reconstruction period addressed how the eleven seceding southern states would regain what the Constitution calls a “republican form of government” and be re-seated in Congress; it addressed the civil status of the former leaders of the Confederacy, and the Constitutional and legal status of freedmen, especially their civil rights and whether they should be given the right to vote. Intense controversy erupted throughout the South over these issues….Congress removed civilian governments in the South in 1867 and put the former Confederacy under the rule of the U.S. Army. The army conducted new elections in which the freed slaves could vote, while whites who had held leading positions under the Confederacy were temporarily denied the vote and were not permitted to run for office (Reconstruction – Wikipedia).

Needless to say, it is important to note, as referred to above, that many of the federal policies during the post Civil War Reconstruction Era were needed and appreciated regarding the rights of freed slaves. And it is also important to note, then, that what is critical regarding federal government intervention, as Trump is wanting, is the policies and/or political orientation of the federal government itself. If the orientation of the federal government is oppressive of the rights of all the people, then the last thing the majority of the people would want is federal troops coming into their states.

The Compromise of 1877: When, in 1877, there was a highly contested presidential election between Democractic candidate Samuel Tilden from New York and Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, a compromise was generated between the southern ‘Democractic’ delegation and the northern ‘Republicans’. This became known as the “Compromise of 1877“, in which the south agreed to support the Hayes presidency in return for the removal of the federal troops from the South (Compromise of 1877 – Wikipedia).

In other words, the southern elite wanted to once again have controlling interests over the freed slaves and everything else in the South without federal interference.

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878: The compromise between the northern and southern political parties, then, led to Congress passing the Posse Comitatus Act in 1878. “The purpose of the act… (was) to limit the powers of the Federal government in using its military personnel to enforce the state laws” (Posse Comitatus Act – Wikipedia).

There are exceptions, however, to the Posse Comitatus Act. If a state chooses to violate its citizens’ rights under the constitution and/or federal laws, federal military troops can then be sent in. This was the case when President Eisenhower sent troops to Arkansas in 1957 to enforce the Supreme Court’s “Brown v Board of Education” decision to integrate American schools. Eisenhower, reluctantly, I might add, responded to the obstructive opposition by the arch segregationist, Arkansas Governor, Orval Faubus. JI Military Police 3: U.S. Troops in Little Rock, Arkansas 1957 (History.com)

JI Military Police 3: U.S. Troops in Little Rock, Arkansas 1957 (History.com)

Since the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, therefore, the U.S. government has been constrained overall in the use of military force domestically in any of the U.S. states.

This constraint, though, has never been the case in U.S. international policies and, therefore, the U.S. has engaged in militarizing the domestic arenas of other countries that fall under the auspices of the U.S. empire or areas of interest (such as the Philippines, South American countries, the Middle East, etc.).

Low-Intensity Conflict (LIC) is a “Policing/Militarization of the U.S. Empire”

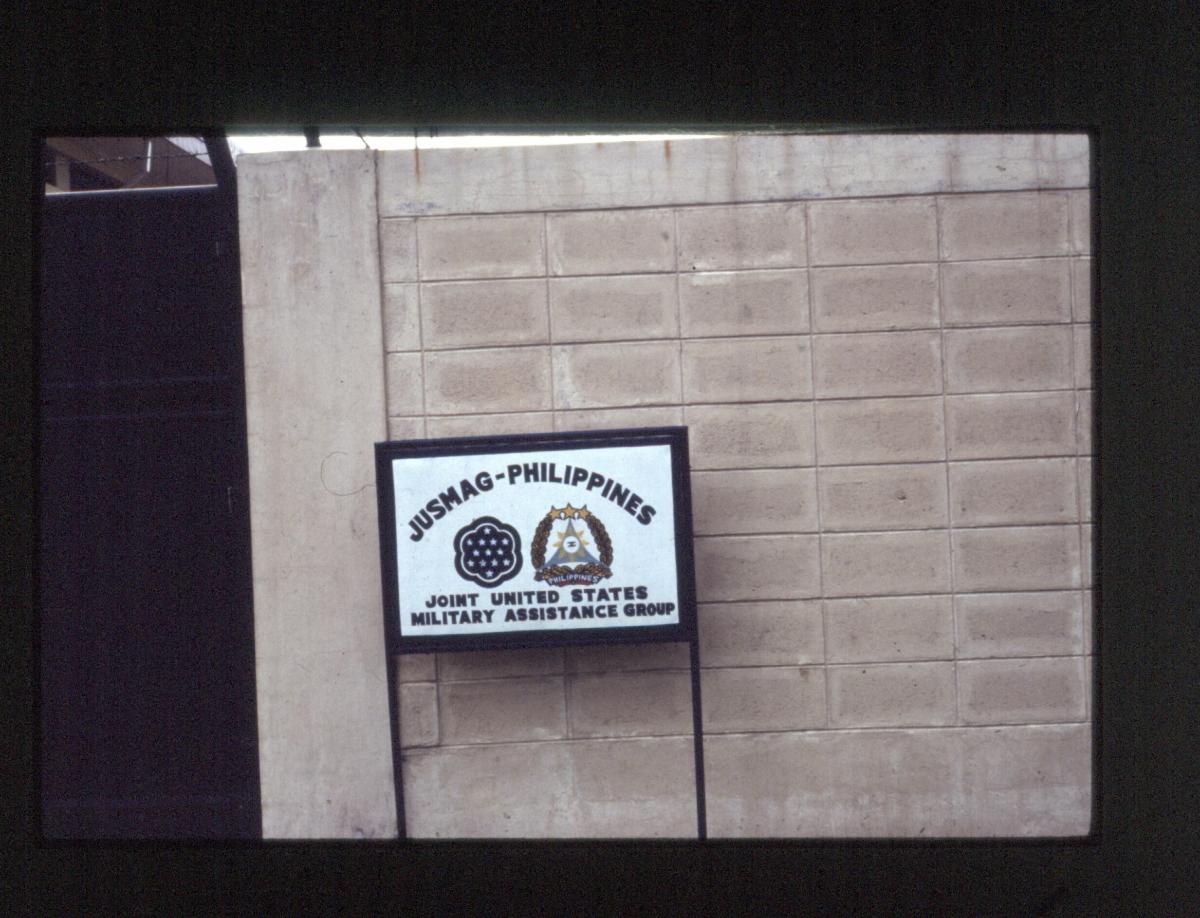

What is “Low-Intensity Conflict”? There are seemingly many definitions of the term. Regarding the impact of LIC on the U.S. personnel, however, I refer to it as “low-intensity” only for the U.S. military and/or the controlling elite. In other words, the U.S. military does not get its hands dirty nor is it violently impacted by LIC, but instead it trains others to do this insidious work. JUSMAG- Philippines headquarters in Manila 1989

JUSMAG- Philippines headquarters in Manila 1989

(JUSMAG – Joint United States Military Assistance Group) (Photo – Heather Gray)

“Low Intensity Conflict” is simultaneously “high intensity” for those outside the U.S. who are victims of these U.S. international LIC policies. These victims are often under intimidating surveillance, sometimes suffer or are killed by summary execution, torture, displacement etc. by military or police in their own country who are often trained philosophically and militarily by the U.S.

In other words, LIC is a method employed to “police/militarize” the U.S. empire on behalf of U.S. political and economic interests. This could also be referred to as “war capitalism” (Beckert).

After the Philippine-American War, the Philippines became a colony of the United States. This was the first imperial venture by the United States outside its hemisphere and it set the tone for the 20th century policies in other countries including those in South America, Africa, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. These other countries were not ‘colonies’ but are ‘countries’ the U.S. has had an interest in and/or has wanted to make sure the governments complied to U.S. trade policies or other economic interests.

In 1901, then, the U.S. created of the Philippine Constabulary (PC) to perform LIC policies and intimidate the existing Filipino revolutionaries. It is still in existence today. (Philippine Constabulary – Wikipilipinas)

It was created under the Commission Act No. 175 by Captain Henry T. Allen, an American, who was later dubbed as the “Father of the Philippine Constabulary”. It was first named as the Insular Constabulary and later renamed to Philippine Constabulary in December 1902.

The Constabulary was the first of the four service commands of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. It was a gendarmerie-type police force (armed police force or a militarized police force) to replace the Spanish Guardia Civil (Spanish Civil Guard – Wikipedia).

The Constabulary was later integrated with the municipal police force, (to become the) Integrated National Police (and then) into the current “Philippine National Police” on January 29, 1991.

In layman’s terms, the militarized Philippine Constabulary has served in the interest of the U.S. and Filipino elite against the revolutionary movements in the Philippines that would, for example, choose to rid the country of its exploitative corporate and military ventures. At the very least, the revolutionary movements throughout Philippine history have attempted to end a government that relies so heavily on and adherence to the United States dictates. (Read the history of the Hukbalahap in the mid 20th century and/or the New Peoples Army (NPA), and about the National Democratic Front in the Philippines in the excellent book The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance by Daniel Schirmer and Stephen Shalom).

Michael McClintock describes an example of the Constabulary military actions in the 1950s:

The combined army and Philippines Constabulary (PC) force level rose dramatically from 32,000 at the beginning of 1950 to 40,000 in 1951 and 56,000 in late 1952. Air power, too, became increasingly important as U.S. assistance stepped up, with some 2,600 bombing and strafing runs reported between I August 1950 and 30 June 1952 alone (some sorties allegedly with support from U. S. planes out of Clark Air Force Base). Requests for napalm were initially turned down on State Department advice, but from late 1951 American napalm was supplied and used both for crop destruction and antipersonnel purposes. A record system devised for Philippine military intelligence, which traced all known supporters of the wartime Huk resistance movement, was operational by the end of 1950; according to one source, it was used in screening operations that resulted in some 15,000 arrests in the first six months of 1951 (McClintock).

In other words, regarding the Philippine Constabulary, there is a fine distinction, if any, between what is “policing” and what is “military” operations.

On-Going U.S. International “Low-Intensity Conflict” Policies

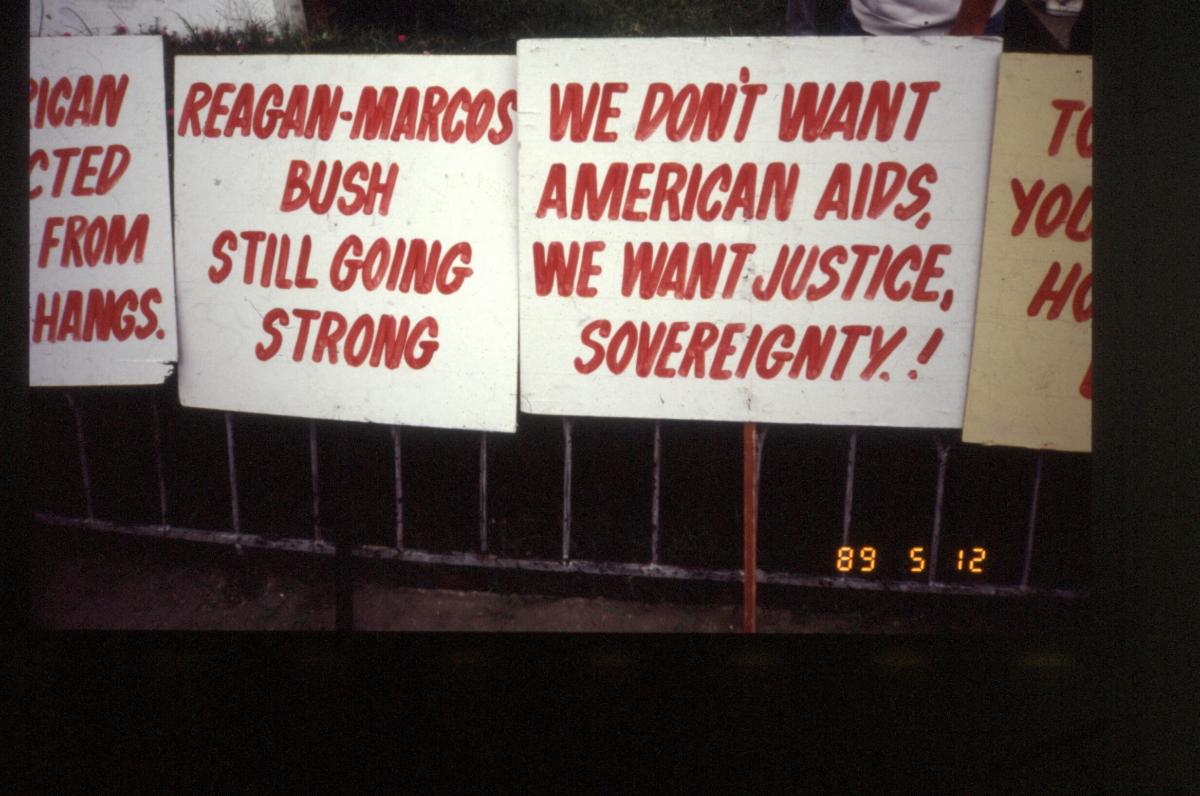

When militarizing the domestic arena of its areas of influence in the world, the United States, as mentioned, pays no attention to its own domestic laws as a model that do not easily allow for this militarization in its own domestic sphere. Signs in Manila, Philippines 1989 (Photo – Heather Gray)

Signs in Manila, Philippines 1989 (Photo – Heather Gray)

In fact, international LIC policies have been implemented by the United States throughout much of the 20th century. The Philippines is just one example. Regarding LIC in South America, we need to consider the U.S. School of the Americas (SOA) or what is now referred to as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC). Founded in 1946, it is located in Fort Benning, Georgia. In this school, the United States trains the military of South American countries to serve a somewhat similar role as the Philippine Constabulary and/or even more violent and extreme, if that’s possible. Filipino army officers have also been trained at the SOA.

We could say that the WHINSEC in the U.S. is training the South American military to fight against their own people, as is true with the Philippine Constabulary.

So, instead of the United States military going into El Salvador, Nicaragua, Columbia, Argentina, etc. the U.S. trains troops from these countries to serve the interests of the United States and the friendly elite of the South American countries. Again, it is a “policing” or “militarization” of countries in what the United States considers its empire of interest.

The “School of the Americas Watch” has a sizable listing of human rights violations committed by graduates of the SOA/WHINSEC. In fact, the “School of the Americas Watch” is under the leadership of Father Roy Bourgeois who has for years wisely tried to close down this school.

One example, below, of these human rights violations is by the SOA graduate General Juan Orlando Zeped from El Salvador who took a course at the SOA in 1975 on “Urban Counterinsurgency Ops”.; and in the 1969, the “Unnamed Course.” Below is some information about General Zeped’s tragic behavior:

Jesuit massacre, 1989: (Zeped) Planned the assassination of 6 Jesuit priests and covered-up the massacre, which also took the lives of the priests’ housekeeper and her teen-age daughter. (United Nations Truth Commission Report on El Salvador, 1993) Other war crimes, 1980’s: The Non-Governmental Human Rights Commission in El Salvador also cites Zepeda for involvement in 210 summary executions, 64 tortures, and 110 illegal detentions. (Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador) Member of the “La Tandona” and held the rank of colonel and served as the Vice Minister of Defense at the time of the massacre. Prior to the massacre he publicly accused the UCA of being the center of operations for the FMLN and was present for the meetings where orders were given for the massacre. He was later promoted to the rank of general (Notorious Grads – School of the Americas).

The Domestic Military: Contemporary Police Departments and Militarization

I have always assumed that the U.S. would also want to implement the LIC strategies domestically or have increased domestic militarization in the U.S. as well, that, as mentioned, the Posse-Comitatus Act has largely prevented. So, rather than sending in the U.S. military into the cities, one way the U.S. has managed to circumvent Posse-Comitatus is to “militarize” the local domestic police forces, which is now happening to a significant degree in the United States. It’s also another way to increase the huge U.S. military budget, as the domestic police departments are obtaining left over military equipment, as if that’s what we want or need in our cities!

In many ways, the militarization of police departments affords the opportunity for the police to “fight against” the American people rather then serve in the “interests” and “protection” of the American people. This is similar to the U.S. LIC trained military recruits in South America and elsewhere.

In a 2014 article on Alternet, Art Kane states:

The “war on terror” has come home-and it’s wreaking havoc on innocent American lives. The culprit is the militarization of the police….

A recent New York Times article by Matt Apuzzo reported that in the Obama era, “police departments have received tens of thousands of machine guns; nearly 200,000 ammunition magazines; thousands of pieces of camouflage and night-vision equipment; and hundreds of silencers, armored cars and aircraft.” The result is that police agencies around the nation possess military-grade equipment, turning officers who are supposed to fight crime and protect communities into what look like invading forces from an army. And military-style police raids have increased in recent years, with one count putting the number at 80,000 such raids last year (Kane).

Art Kane‘s “11 Shocking Facts About America’s Militarized Police Forces” are:

1. It harms, and sometimes kills, innocent people.

2. Children are impacted.

3. The use of SWAT teams is unnecessary.

4. The “war on terror” is fueling militarization.

5. It’s a boon to contractor profits.

6. Border militarization and police militarization go hand in hand.

7. Police are cracking down on dissent.

8. Asset forfeitures are funding police militarization.

9. Dubious informants are used for raids.

10. There’s been little debate and oversight.

11. Communities of color bear the brunt.

Included in the concerns about militarized police forces should also be about information the training police officers receive altogether, as in attitudes and justice toward the other.

Kane provides an excellent narrative for each of the above facts. I witnessed virtually all of these “11 shocking facts” in the Philippines in 1989. They are now, unfortunately, to be witnessed in the United States as well.

The unfair and disastrous “Low-Intensity Conflict” policies forced on many other parts of the world have come home to roost.

Summary

It is encouraging, however, that there is now significant organizing in the country against this trend of police militarization and gun violence overall. It needs to also be extended as well to the countries throughout the world that are continuing to be victims of these U.S. “Low-Intensity Conflict” policies. Closing down the School of the Americas would also be a good first start and implementing policies that do not allow for a militarization of our police departments would be another, and should be addressed with all deliberate speed. Many American police have also been trained in Israel and this should end altogether.

Americans also need to address the training American police departments are implementing with the domestic police recruits and police staff altogether. For example, how much of the low-intensity conflict model is being implemented. In other words, is the violence by the police used to service the corporate and elite interests in America? And further, is the training racist, biased, altogether encouraging discriminatory behavior and the use of force by the police throughout the country.

When Martin Luther King said “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” he was certainly correct by inferring that injustices conducted by the U.S. elsewhere will come home!

Gray & Associates, PO Box 8048, Atlanta, GA 31106