Editor’s note: This interview was conducted on April 29, 2000 with five residents of the Osage Avenue neighborhood which had been the scene of the May 13, 1985 bombing of the MOVE Organization. The interview has been edited for length, and the names of the interviewees were not recorded to ensure their privacy. The text had been saved on an old computer hard drive and was only recently recovered.

Editor’s note: This interview was conducted on April 29, 2000 with five residents of the Osage Avenue neighborhood which had been the scene of the May 13, 1985 bombing of the MOVE Organization. The interview has been edited for length, and the names of the interviewees were not recorded to ensure their privacy. The text had been saved on an old computer hard drive and was only recently recovered.

I’ve had the last 16 years since the interview (and a couple of years before that) to meet and talk with members of MOVE, particularly Mama Ramona Africa and Mama Pam Africa, and to see the integrity of the members of the MOVE Family, as well as their compassion and affection for those who would go so far as to simply listen to them. Over the years, MOVE may have “softened” their approach (not as many swear words, for example), but they have never wavered in their commitment to resisting this “rotten-ass system”. I pretty much understood this even back then on April 29, 2000 when I sat down to interview the five gentlemen on Osage Avenue, but still, I wanted to be sure they had their say. And the more they said, the more I saw that their concerns were not that different from those of MOVE, even though they disagreed with, and at times even condemned, MOVE’s methods. I hope that understanding comes through as you read the interview below.

Interview at Osage Avenue

April 29, 2000

There are a number of articles on this website that describe the ongoing struggles of the MOVE Organization from the MOVE perspective, as well as links to the MOVE site. While we at KUUMBAReport would not personally practice every tactic, strategy and philosophy of MOVE, we agree with them in general and remain committed to defending MOVE’s right to live their lives as their philosophy has determined to be in harmony with their beliefs and their convictions. We call for justice for the six adults and five children who were victims of the 1985 MOVE bombing and for the hundreds of neighbors who lost their homes and faced a protracted struggle to make their lives while again. We call for justice and full vindication for Mama Ramona Africa, the sole adult survivor of the bombing, and the members of the MOVE Organization who were forced to endure the violent deaths of their family members that day. We advocate for the immediate release of the imprisoned members of their family, the MOVE Nine (seven of whom still are alive in prison since the 1978 Powelton Village assault by Philadelphia police) and for the exoneration and liberation of their best-known defender, journalist Mumia Abu-Jamal. But there was one perspective I had always wanted to hear, that those of us who support revolutionary struggle rarely have an opportunity to truly engage with – that of the “average citizen” who does not share the “revolutionary” philosophy and who might be strongly critical of it, but who might actually share more with us than we would expect.

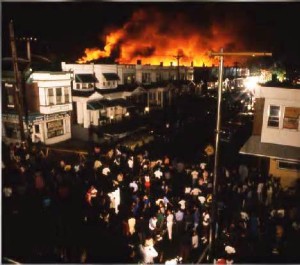

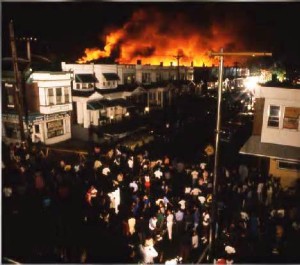

On April 29, 2000, I visited the Osage Avenue neighborhood where the infamous MOVE bombing took place. Fifteen years after an entire city block of 61 houses was burned down and eleven people – six adults and five children – were killed, the houses had been rebuilt, some of them several times over. A friend of mine from my daytime employment had grown up in Philadelphia, and as we had debated the fear he had expressed of the MOVE Organization, I had been able to disabuse him of most of his misconceptions. As a result, he had gotten me in touch with someone who lived in that Osage Avenue neighborhood and, through contacting this person, an interview with several people who had a rather unique perspective on the confrontation was arranged.

I did not record the names of the interviewees on the audiotape, in part to protect their identities in case any of their opinions were considered too controversial to ensure their privacy. I have instead listed them as “Mr. A”, “Mr. B”, “Mr. C”, “Mr. D” and “Mr. E”. These were five gentlemen who lived in the Osage Avenue  neighborhood at the time of the MOVE bombing on May 13, 1985. Their opinions regarding MOVE were at least somewhat varied. Some were more sympathetic to MOVE than others. They all agreed that their perspectives were different from that of MOVE, and thus they generally did not approve of MOVE’s methods of confrontation. They also agreed, however, that what happened to MOVE, from the Osage Avenue bombing to the Powelton Village confrontation in 1978 to the years of abuse they had suffered at the hands of the Philadelphia Police Department, was undeserved and was the result of the actions of a corrupt, racist and repressive system. They also made several allegations regarding the conduct of the 1978 and 1985 police actions and the subsequent investigations that some might consider shocking.

neighborhood at the time of the MOVE bombing on May 13, 1985. Their opinions regarding MOVE were at least somewhat varied. Some were more sympathetic to MOVE than others. They all agreed that their perspectives were different from that of MOVE, and thus they generally did not approve of MOVE’s methods of confrontation. They also agreed, however, that what happened to MOVE, from the Osage Avenue bombing to the Powelton Village confrontation in 1978 to the years of abuse they had suffered at the hands of the Philadelphia Police Department, was undeserved and was the result of the actions of a corrupt, racist and repressive system. They also made several allegations regarding the conduct of the 1978 and 1985 police actions and the subsequent investigations that some might consider shocking.

Interviewer – Bro. Cliff (KUUMBAReport)

Interviewees – Mr. A, Mr. B, Mr. C, Mr. D, Mr. E

KUUMBAReport: We’re here in the 6200 block of Osage Avenue and we’re talking about the history of the MOVE Organization in this neighborhood as it led up to the 1985 bombing, and even some issues that might have come out since then because I’m sure that wasn’t the last anyone heard of the MOVE Organization. What was the first time that people had heard in this neighborhood about MOVE, and what were the first impressions of people about them?

Mr. B: Well actually we had heard about MOVE prior to this experience that we had with them – back in Powelton Village. At the time, I just figured it was one of these radical groups, from what I’d seen in Powelton Village. … But I really didn’t pay that much attention to MOVE then, not until we had this experience. I don’t care what your religion might be or whatever. That’s yours. But don’t infringe it on me. If I don’t want to listen to your [political or religious agenda], then that’s my prerogative. They just seemed to have this thing where their people were in jail, but that didn’t have anything to do with holding us prisoner because their people were in jail, which we had nothing to do with. And we had a lot of elderly people around here, kids and whatever, and their lives were in jeopardy, they were in danger, and to me, I just lost all respect for them.

Mr. A: They told us, basically, “if you don’t help us, we’re going to irritate you so bad that the police are gonna come in,” but then what happened, we used to call the police, and the police used to say “we’re not coming in there. We can’t come in there. And you better not go in there messing with them. Just leave it alone.” A hands-off situation.

KR: Was this during Wilson Goode’s administration?

Mr. A: It was during Wilson Goode’s administration, when he got in office, because we had a meeting with him downtown one day and I remember, I said “Why don’t you do like [former mayor Frank] Rizzo did – just knock down the whole building?” He went off on me. He said “I’m not gonna do nothing.”

KR: Of course he wound up doing something even more extreme.

Mr. E: But what happened is, if you were following it very closely, he was pushed into it politically because who really pushed the button, and people don’t realize it, is Joan Spector. She pushed Wilson Goode to the point where he had to try to do something. She was a city councilperson; Arlen Spector’s wife. What happened was, Wilson Goode, before he turned it over to [police commissioner Gregore] Sambor, he kept putting it on the news, “Anybody with any peaceful solutions, please step forward and try to do something,” so people came through here and talked to them through the window and all of that kind of stuff, and so then, when he put it in the White man’s hands, that was it.

KR: So, once he turned it over to Sambor…

Mr. A: See, when a Black man says “I’m gonna kill you,” it doesn’t mean the same thing as when a White man says “I’m gonna kill you”; he literally is gonna kill you. We use that term all the time, “I’m gonna kill you.” It’s not the same.

KR: They’ll kill you for real.

Mr. A: That night just before the MOVE thing busted off, that was Sunday night, they were up there, MOVE people were saying that they were going to kill the White cops and all that. Getting into “The Dozens”.

KR: I understood that MOVE took the art of talking stuff to a new level.

Mr. A: That was a political thing to keep it hyped up. See, because they wanted a confrontation to try to get the people on their side. The whole issue, the whole thing boiled down to one thing – getting their people out of jail, and it’s still like that. That’s what it’s all about.

Mr. A: That was a political thing to keep it hyped up. See, because they wanted a confrontation to try to get the people on their side. The whole issue, the whole thing boiled down to one thing – getting their people out of jail, and it’s still like that. That’s what it’s all about.

KR: Because their people are still in jail. The MOVE Nine are still in jail and one of them died [Merle Africa, 1998 – Editor].

Mr. E: That’s the whole issue. … But the deal is, if you go to war and you lose, hey, you’re fighting the system. You can fight the system like the NAACP, b.s.ing, or you can physically fight the system. And the NAACP is a good example because they spend a lot of money – they really don’t do that much, in my opinion anyway. What’s gonna happen, if you get back to the 60’s and all that stuff in my era, if you really checked it out, the people who really made the difference – they gave Martin Luther King the glory, because he was always talking about peaceful demonstrations … but the little communities … had the same agenda, “hey, I can’t work for these wages. I’m tired of these White people doing this to me.” Everybody was on the same accord. But … he was holding the Blacks back. Same thing in South Africa, Tutu, he was always “peaceful demonstrations”, they let Mandela out. [But] they’re worse off now with him being the president. Only thing he did was put a buffer on those Mau-Maus and the Zulus, they would have took over Africa. … And that’s what people don’t understand, these so-called Black leaders. And then after the civil rights thing in the 60’s, all these so-called preachers, “Oh, we’ll teach [you] how to be a carpenter, we’re going to go through all these programs and the money trickles down”; we don’t learn crap. The White people are still controlling, they’re still making all the money.

KR: It almost sounds like the philosophical argument between, say Booker T. – cast your bucket down where you are – and Garvey – the whole Pan-Afrikanist concept.

Mr. E: I was in church today, and this minister said something today that really blew my mind, and I said “Good, Blacks are finally coming out and saying the truth.” He was talking about Ethiopia and he was saying Jesus was a Black Ethiopian, he was a Black man. They don’t even teach that, the Bible was written about Black people basically, but Black people are never mentioned. So, everybody has an agenda, like MOVE has an agenda, but what makes a revolution is when everybody gets on the same accord, and they’re thinking the same way, “I ain’t taking this crap no more.” I don’t have to tell you, you don’t have to tell me, we just wake up one morning and you say “No, I’m not gonna do this no more,” and then that’s what the revolution is, the same thing is in everybody’s mind. But what the White man, the media does, he tries to pick the one that’s most peaceful; “hey man, let’s talk.” Just like Malcolm X; “let’s not do this, no.” The only way you get anything in the end is physical force, when you’re dealing with Whitey, you cannot make compromises, because he kills you every day. That’s the only way you can do it. That’s just my opinion.

“We were pawns in the game”

KR: I don’t know whether there’s any consensus around any of this or not, but, in looking at say, for instance, the way the MOVE Organization was dealing with whatever their grievances were, would you say that most of the Osage Ave. residents disagreed with the MOVE Organization itself, disagreed with its philosophy, or disagreed with its tactics?

Mr. B: Well, I think both the philosophy and tactics. …

Mr. A: Well, one thing I’ll never forget. It was Christmas Eve 1982. It was the first time we heard the bullhorns because everybody came to the door, and we were trying to figure out, What in the world was going on? All of a sudden we hear these voices and we’re sitting in there, getting ready for the holiday and everybody comes to the door, What was that? First thing they had was a speaker this big [about one foot tall], well that grew to a stadium-size speaker. And I remember, I used to talk to Conrad [Africa] all the time and one day Conrad came up the street, and we were standing out in front of my house, and I was complaining about what was going on, and he told me, right up front. He said, “All of what we’re doing, we’re not doing it because we have anything against you people as neighbors. But we need you to go to City Hall to get these people’s attention.” So we were used; he told me, point-blank. He said “We will use you to get to them.” We were pawns in the game.

KR: Had they ever approached you to ask you for your assistance?

Mr. A: They asked us. My answer to them was hey, I didn’t do it. I didn’t start it. I’m not in your organization. What can I do? You know, I didn’t start none of this.

KR: Did they try circulating petitions or anything like that?

Mr. A: I think they did do that one time.

Mr. E: I never got a clear-cut picture of what they really stand for. I still don’t know. Can you tell me what they stand for?

KR: Basically, what I understand about the MOVE Organization—this is primarily from what I’ve read in some books and some other things—is that essentially, they’ve been described often as a back-to-nature organization, and I don’t know that they necessarily describe themselves that way but that’s probably as close as you can get, at least with a cliché, in terms of what they were about. There were a number of things they did not believe in doing. Supposedly in Powelton Village this led to some difficulties smell-wise because they didn’t believe in the traditional way of, for instance, disposing of garbage. And that led to some difficulties with the Powelton Village neighbors but ultimately, I think, one of several mediators – and I want to ask you about whether any of these outside mediators came through either – I know they came through Powelton Village and they worked pretty extensively; I know Oscar Gaskins was a lawyer, Walter Palmer was a community activist.

What I also understood about them is that there were a number of other things that they didn’t believe in; for instance, one of the things Pam Africa talks about now is Ritalin. It’s being given to, apparently, a lot of children in a lot of public schools, apparently in Philadelphia, I know it’s in Baltimore, it’s in DC. And Ritalin is sort of like Prozac.

Mr. A: It’s to keep them calm?

KR: It’s supposed to deal with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder, and that’s a major cause for her now, so she’s branched out a little bit now from just “Release Mumia, Release the MOVE nine…”

Mr. E: This is what fascinates me too, about this whole setup, you take the kid, you try to change the kid, when the kid comes. You stop it, you get it from the root. The parent is the root. That parent must be re-educated, because you go the malls and stuff. I was up at the Pathmark [grocery store] a couple of weeks ago and this man was talking to his daughter. He said “Look here, little b—-, if you don’t shut up, I’m gonna kick your ass.” I’m serious. This is a man, talking to a little kid, about 8 or 9 years old. That person needs to be re-educated, because people now don’t have any morals. Morals is out. The thing is, “Long as I don’t get caught.” It’s nothing to do with what’s right or wrong.

Mr. A: Well, you know what it is? The things that you are saying is symptomatic of what our society has come to. There doesn’t seem to be any civility out there anymore. It’s like people just don’t care. And you’re right—people need to be re-educated. They need it but they don’t want it. They seem to be satisfied with the status quo. But there’s many of us out there, just like you, that, we’re not satisfied with the status quo. [But] we’re not going to allow people like MOVE to just force their will on us. Everything that we did was within the law. We never stepped out of the boundaries of the law, even up to today.

Mr. E: There’s two laws; there’s man-made law, and there’s nature’s law; God’s law.

KR: Even that’s kind of close to a lot of things that I’ve heard come out in MOVE statements. There’s this one thing that I sometimes get a kick out of whenever this thought comes to my mind but it’s something that I’ve heard a lot, and it’s a quote: “Down with this rotten ass system.” And, basically, what they’re doing is they’re looking at a lot of the same things that we’re looking at, and their claim is that a lot of the things that are going on now in our community are the result of the influence on our minds by the prevailing system.

Mr. A: Can I ask you a question? They say “Down with the system” but did they ever come up with what they had to put in the place of the system that they want to take down? So you can’t take a system down, not unless you’ve got some idea as to replacing it. I’ll put it another way. We have a lot of radical groups in this country. They’re all out west and different places. They get their little cults … down in little villages. Just take your idea and move somewhere else with your little group, and leave me alone. I’m in the mainstream, I’m catching hell in the mainstream, right? But if I don’t really like it, I’ll go down south in the woods somewhere, okay? I’m not going to try to kill everybody off. My point is, if MOVE says “Down with this damn system”, what are you gonna put in its place?

Mr. E: But this system is corrupt and everything…

Mr. A: Well, we know that!

KR: I don’t think MOVE’s problem is even one of not having anything to replace it with, because, technically, if you were to ask any member of MOVE “What would

John Africa

you replace the system with?”, they would say, “We have John Africa’s Guideline.” From what I understand, when John Africa first got a foothold in Powelton Village, he was walking neighbors’ dogs and then the Powelton Village people gave him a house in return for various handyman duties he was performing around the neighborhood, and then Donald Glassey, this White guy, comes in. He’s fascinated with the consistent way John Africa was living his life. And so they sit down, [John Africa] transcribes this Guideline, and it comes out to something like 800 pages long. Next thing you know, members of John Africa’s family are meeting in his house, some of his friends are coming along, and they’re having these study groups around the Guideline, and then that was basically the genesis of MOVE.

Mr. C: MOVE always said that Glassey, who I think was a student or something, was just – he just wrote down what John Africa told him. Glassey had no part in setting any guidelines, or establishing the concept or anything. He was just a viewer.

KR: I’ve also read he turned informant after a few years. Some people think he always was.

Mr. C: Well, I can believe that.

Mr. E: I used to see Glassey every day, I used to work at Temple, I used to go past there every day. And what really kicked off the thing with the MOVE people was they were going pretty good, walking the dogs and all, but when these White girls started hanging around there, that’s when the crap hit the fan.

KR: White girls became attracted to John Africa’s organization and all of a sudden….

Mr. E: Oh yeah, that’s when the crap hit the fan!

Mr. C: But what he’s talking about is a college community. We have our working-class White neighborhoods but …

Mr. E: What’s that campus? What’s that school down there?

Mr. C: Drexel.

Gentrification Looms Over Everything

KR: I think Drexel and Penn were buying up land in the Powelton Village area, so the residents had a beef – that was another thing, the residents of Powelton Village, even though there were a lot of White folks in that neighborhood, they had this major beef with Drexel and Penn gentrifying the neighborhood and they had a beef with Frank Rizzo, because they didn’t vote for Rizzo, they didn’t like Rizzo.

Mr. E: That’s political, same thing with Temple. The community was crying about that. Temple’s all into everything. They’re pushing everybody, they’re just pushing. Now you go down Diamond Street, they got all them White folks living there on Diamond Street. … White folks are gonna take over North Philly. They’re gonna actually take it over. People think you’re crazy when you say it but you watch what they’re doing. Now, [year 2000 Philadelphia Mayor John] Street, Wilson Goode and a couple other of the politicians and [prosecutor and future Pennsylvania governor Ed] Rendell, he went in with it, now they got these new homes they built down there, right off of Girard Avenue, around 15th… they got all these new homes around there. But see, they’re making these houses so high, the prices are gonna be so outrageous for Blacks, who’s gonna buy them?

Mr. C: Well, what do you think they’re trying to do around here?

Mr. E: Sure, it’s the same thing. All the White folks, they’re coming back into the city, because it’s too long a drive, they’re tired now.

KR: So the whole city’s basically being gentrified.

Mr. E: Sure, sure.

Mr. C: Yeah, it’s too high. … Except for this area right here. This area right here, that they call Cobbs Creek. This has 80% Black home ownership, and it’s the largest Black neighborhood in the city. It’s larger than Mount Airy, and all the rest of them. There’s no place else that you have a Black neighborhood where you have 80% Black home ownership. But the reason they can come into other neighborhoods is because of the lack of home ownership. Because a lot of times we are in places where we are renting, so we don’t have control over who comes in and takes over the properties. Here, they would like to come in here, but we’re not moving out, as a community. Because it’s a nice area, you’ve got the park, you’ve got transportation, you’ve got everything that anybody would want in a community.

Mr. A: Really it started coming back in the latter part of the 70’s. When I moved in, in 1976, that was the beginning, because I think that the interest rates were down to about 9 percent … and the interest rate I remember because a buddy of mine – I was saying “man, you better buy a house.” The interest rates went up to about 18, almost 20 percent.

Mr. E: Mine was about 5¾ when I bought mine.

Mr. C: There was a 6% interest rate back in around ‘70.

Mr. E: But I remember there were 4 houses over there, right?

Mr. A: In this general area there were about 8 houses that were empty, I remember. So, the whole area, there was a whole bunch. You can’t find one in this area now.

Mr. B: What it was back then, in the middle 60’s and early 70’s, you had the city, they wanted to come in here … and they wanted to run an expressway through here. So what they were doing, the city wanted to buy up all this land, all these houses around here … so what they were doing was trying to get the Black people so that they would move out of here. … Redlined this area. Couldn’t get a mortgage, couldn’t get a loan, couldn’t get anything. And, whatever came of it, I didn’t really follow it that much, but at that particular time they said they were trying to lay this expressway in here.

KR: Then you try to destabilize it, you funnel the drugs into this area of the city and then everyone’s gonna run.

Mr. C: And probably because there was so much home ownership, they couldn’t do it. Say, for example, there had been less home ownership, then they could have grabbed up all the houses that Blacks didn’t own, let ‘em go down so that the people that did own homes didn’t want to live next to this abandoned house – this is the way they’re doing it in north Philly – they just put everybody out, let the house go down, or let somebody live in there but the house is still going down. …

The Lack of Common Ground between Neighbors and MOVE

KR: The way it kind of looks to me, it looks like a lot of the things that we’re concerned with in general, are actually a lot of the same things MOVE were concerned with, but for whatever reason, they didn’t know how to make their point [to you].

Mr. A: The real problem we had with MOVE was they were selfish in what they wanted to do. The only concern they had was the concern for what was theirs, and what they needed to do. They weren’t concerned about our right to pursue happiness, our right for our families to be safe and secure. They had one agenda and that’s really what angered us. It wasn’t the fact that we didn’t want to help them. I feel as though if they had approached us in the right way, we may have been willing to assist them. But they forced themselves on us. They forced us into the middle of a conflict that we had nothing at all to do with. They forced us, and that’s the problem we really had with them … their back-to-nature situation, they forced this on us. They made us feel like we didn’t have a right to live. They had all the rights in the neighborhood and we weren’t going to allow that. So that’s where our problem really came in with the MOVE people.

KR: I guess part of the problem here is that, in order for agreements to come between MOVE and the neighbors of Powelton Village, you still had to have third-party intervention, so it wasn’t a situation where the two sides were going to see eye-to-eye just left to their own devices, because I’ve read about a number of the third-party interventions. I wrote some of the names down so I wouldn’t forget them – but it seems to me from here, and I don’t know how effective they were on Osage Avenue, but Walter Palmer and Oscar Gaskins seem to be the closest ones in Powelton Village to actually settling anything, because I think they had helped to broker a composting agreement with Powelton which basically had MOVE taking their garbage and cycling it in their backyard. The smell problem went down, the rat problem went down, MOVE got exercise, they sold compost to the neighbors. In other words it was something that the Powelton Village organizations and MOVE ultimately agreed on and that actually started to ease tensions in that area, but by then Rizzo had already instituted the blockade.

Mr. B: We didn’t have that here.

Mr. A: We had no intervention. We were left standing alone. We wanted the city, they didn’t want us. We wanted the politicians. They came in and they lied to us. So we were virtually left standing alone, fighting against something, we really didn’t know, from one moment to the next, what was gonna happen or what was gonna go on. But we knew one thing: we were gonna protect our families, at whatever cost it might take.

Mr. B: Not only that, when MOVE first entered the block, you would see maybe one or two of them. You didn’t pay them any attention. And as time went on and you started seeing more and more of them, moving into the house over there; this is, I would say, a pretty middle-class neighborhood here. Everybody tries to take care of their property. Then all of a sudden you turn around, you see boards being put all up on top of the houses, windows being boarded up, the driveway back there – this is a driveway for everybody that lives on that side of the street. Why is it that one family can say “this is mine, you can’t use it”? They didn’t take into consideration the other neighbors.

Mr. C: What Mr. B is talking about is, they blocked off the driveway from their property line on one side to their property line on the other side, because they were picking up all the stray dogs in the community. So they would start feeding them all kinds of raw meat and stuff, out in the driveway … but the stuff that wasn’t eaten, then the rodents came because you got the field mice and everything coming up, roaches and everything. … An exterminator could have bought an apartment on the block, if it was an apartment complex, and lived there and paid rent based on just going up and down. Because you would always have to keep going because there was nothing that they could do to stop the rodents from coming in because of the way they dealt with their feeding of these animals. Although they got out and they swept the fronts and they were clean in their own way, but then they were dirty in our way, because we’re not going to leave food and stuff out in the driveway because we know that that’s going to bring rodents.

KR: They were once quoted as saying, “As long as [the rodents] ate good, they didn’t bother us” in Powelton Village before the composting agreement. So it almost sounds as though, even though they had succeeded in coming to a composting agreement in Powelton, when they came here to Osage, they didn’t have that same practice when they got here automatically.

Mr. C: I think, here, it was different than down there. Down there, the city went to them, because that is like what we were talking about a little earlier. That’s rapidly being taken over by Drexel University. So that’s a Black area that the university and the city were trying to make White through expansion of the university. So the city wanted them out, so they would use whatever techniques available under the law such as health codes and this, that and the other.

KR: Did that make independent mediators more likely to try to get involved there too, because they had a concern over what Rizzo might do to them, or what Rizzo might do to the entire neighborhood?

Mr. C: I don’t know, but I think that that’s a good possibility because I think the Black community didn’t trust Rizzo because he had alienated himself from the Black community…

The Notorious Brutality of the Philadelphia Police Department

KR: Well, the regular police were called “Rizzo’s Thugs”. Amnesty International said they were the most brutal police force in the country, bar none.

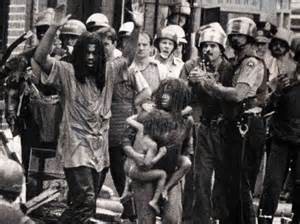

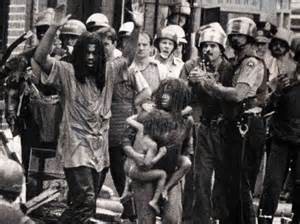

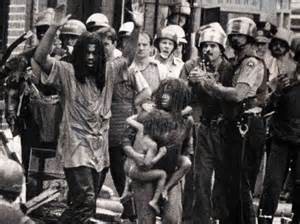

The MOVE Nine after the 1978 assault.

Mr. C: I was on the police force myself, when Rizzo became commissioner. I was on there before he became commissioner, and I was on there when he became commissioner. And his philosophy was, shoot first, ask questions later. His philosophy was, a show of force, and if anybody had to use force he was going to back them up.

KR: So this started when Rizzo came into power?

Mr. C: Right, exactly. And so, the general feeling of the members of the police force is that they were above the law when it came to using deadly force because they thought that nobody on the police force was going to be disciplined. If you shoot someone unnecessarily and they die, it wasn’t going to be a problem. I’ve witnessed cases where unnecessary shootings were rewarded, so that the officers who did it were promoted.

KR: Well, you had something like that in Louisville last year, where an unarmed man was shot by police officers. The police chief, later that year had an awards banquet where he gave, among others – not just these two – but among other officers, he gave these officers medals, and the mayor turned around and fired the police chief for that, and then immediately after that, the rank-and-file police in Louisville started protesting, and they called it a “slowdown” where they stopped making as many arrests. The strange thing about it was that the number of arrests went down but the crime did not go up!

Mr. C: That proved the point that they were wrong from the beginning.

KR: And the community said “You’re not going to protect us!” And they said “Well, the slowdowns that we’re making in our arrests are, we’re not doing the kind of proactive policing that we were doing before.” So now it seems that the cliché has gone from “zero-tolerance” to “proactive policing” where if you’re reaching for your wallet, you may be reaching for a gun, let’s shoot you 19 times.

Mr. A: [Amadou] Diallo.

KR: Yeah, and Patrick Dorismond also. “You won’t tell me where the marijuana is?” Bang!

Mr. C: We had a guy around here, Dante Dawson, he was shot; remember that time, right when he’s sitting in his car. Very extreme – I mean, it’s not extreme by police standards, but it’s extreme by our standards because he was unarmed. He was asleep in his car, and when they approached him and he didn’t respond the way they ordered him to, although he was unarmed, then they opened fire on him.

KR: One of the things I read in some of these books is, actually, there was a difference between the regular police, who were the ones who have been accused of brutality, and George Fencl’s group, and they were considered a much more professional unit.

Mr. C: They were just an undercover unit. I worked undercover before. They’ll take, maybe, whoever they think might be good for undercover. They may take sharpshooters or something like that, put them in undercover, like narcotics or any kind of vices. They were like a vice squad. Gambling, prostitution, whatever. Fencl was the captain of an undercover unit, and they operated in a certain way. He got a lot of notoriety and a lot of acclaim for his results. Just an undercover operation that might have gotten a lot of publicity, but his people were taken from the general population of the police force. They weren’t like specially groomed for that. They just, maybe, had specific talents that could be utilized in something like that.

KR: So, was it maybe by virtue of the kinds of assignments they had or do you think it might have been by virtue of the kind of atmosphere they were working in that they didn’t get the same reputation as the regular police?

Mr. C: It was just because … the regular police weren’t on undercover, so they didn’t do, say maybe the large scale busts that Fencl’s group might do. They weren’t doing it on a regular basis like Fencl’s people. …

KR: But Philadelphia had gotten a pretty strong reputation for excessive force …

Mr. C: Brutality. Say for example, Rizzo, when I think he was commissioner, we had a situation where the schoolchildren felt like they were not being educated properly and they were protesting in front of the school administration building on Ben  Franklin Parkway in center city. So Rizzo ordered the police to go in there with horses – it was the type of thing reminiscent of the protest marches in the South when they had the dogs and the horses and everything; I don’t think they had the water hoses but I think they had dogs and I know they had horses, and what they did was they beat up on school kids. So they treated the school kids, they didn’t treat them like they were school kids, they treated them like they were criminals. So I think that was one of the first instances of how bad our city police force could be when they would not understand how to handle school age children, when they would handle them the way they would handle hardened criminals. Rizzo had a reputation from when he was just a regular police officer as being a macho type of person. And so when he became police commissioner he just carried his reputation on and expanded it throughout the whole police force. And then you had those who had that mentality on the police force, adopted Rizzo’s tactics of brutality, especially when they knew that they weren’t going to be penalized. You had a whole lot of times when a guy had been arrested – he was stopped and they gave him a ticket, and maybe he was disorderly and so they arrested him. Then, a couple of hours later, he would be found hung in his cell. It was like more than a couple of occasions that that happened. They had a case where, down by the police administration building, a guy was arrested for stealing a car. And when they went to take him out of the police wagon to take him into the police administration building, he ran. Still handcuffed behind his back. So the police ran up on him, shot him in the head and killed him.

Franklin Parkway in center city. So Rizzo ordered the police to go in there with horses – it was the type of thing reminiscent of the protest marches in the South when they had the dogs and the horses and everything; I don’t think they had the water hoses but I think they had dogs and I know they had horses, and what they did was they beat up on school kids. So they treated the school kids, they didn’t treat them like they were school kids, they treated them like they were criminals. So I think that was one of the first instances of how bad our city police force could be when they would not understand how to handle school age children, when they would handle them the way they would handle hardened criminals. Rizzo had a reputation from when he was just a regular police officer as being a macho type of person. And so when he became police commissioner he just carried his reputation on and expanded it throughout the whole police force. And then you had those who had that mentality on the police force, adopted Rizzo’s tactics of brutality, especially when they knew that they weren’t going to be penalized. You had a whole lot of times when a guy had been arrested – he was stopped and they gave him a ticket, and maybe he was disorderly and so they arrested him. Then, a couple of hours later, he would be found hung in his cell. It was like more than a couple of occasions that that happened. They had a case where, down by the police administration building, a guy was arrested for stealing a car. And when they went to take him out of the police wagon to take him into the police administration building, he ran. Still handcuffed behind his back. So the police ran up on him, shot him in the head and killed him.

KR: We’ve had a number of cases like that in Maryland too. Archie Elliott III, handcuffed behind his back, strapped in the front seat of a police cruiser, and all of a sudden the two police officers claim that they saw him pointing a gun out of the window of the car. Now, how do you do that if you’re handcuffed behind your back, strapped in the front seat? You’ve got no gun because you’ve already been searched. You’re wearing a pair of cutoff shorts, some sneakers and no shirt. You’ve been searched and no gun has been found and yet somehow, you came up with a gun, pointed it out the window of the police cruiser with your hands cuffed behind your back. They shot him 12 times, through the door of the police cruiser and killed him. [Of course, by 2016 there have been countless more atrocities on Baltimore alone, most recently the murders of Tyrone West in 2014 and Freddie Gray in 2015, as well as police murders of unarmed Afrikan-American men and women across the country, and certainly many more will come to light as the year goes on – Editor.]

Mr. C: That’s the type of thing that was happening. With the case that I just mentioned, it was found that the young fella owned the car. It was his car. He was just afraid. He was intimidated by the police. And rightfully so, because of what happened to him. He knew that this is how it was. So he didn’t want to be in the building with these police, not knowing what they were going to do to him, and tried to make a getaway. But the fact that they had to shoot him, with his hands handcuffed behind his back, tells you something. So that was the atmosphere during the Rizzo years.

KR: And in the middle of all of this, up pops MOVE.

Mr. C: Right. So MOVE didn’t care about Rizzo or none of his police, and they were back-to-nature, but they were also anti-government. And I think the main thing with MOVE, I think everybody, for the neighbors here, I think we all agreed that they had a right to their own opinion and a right to their own way of life, but we didn’t think they had a right to involve us in their plight, although they said it’s all of our plight, but we felt that we had a right to fight the official oppression the way we chose. We didn’t think it was right to force us to have to do it the way that John Africa dictated, because we didn’t all subscribe to John Africa. I don’t think there were any neighbors who subscribe to John Africa’s philosophy. They may have agreed with his identification of problems, but maybe his way of addressing it we didn’t agree with. I don’t think any of us would have brought our children into a place that we were having a standoff with the police in. So, we would say well, maybe we’ll take our kids somewhere else, leave them with somebody we would trust, family or whoever, rather than put them in harm’s way. I’ve heard the MOVE people say, “Well, we didn’t want them in the system, and if we didn’t have them with us they were going to be in the system and we’d feel like they were dead anyway.” We wouldn’t have taken that type of outlook on it. We would have said “Well, at least they’ll be alive to live another day,” and maybe they can figure a way to deal with the oppression rather than putting them in harm’s way and not giving them a decent chance to continue their lives. After all, they were children. They should have the right, we felt, to grow up and make their own decisions, once they were mature enough.

KR: You’re referring to their decision to keep everyone together in that house on Osage Avenue, even though they knew the assault was coming?

Mr. B: See, they used us as a shield, the neighbors as a shield, and the children as a shield. Before that confrontation, right before it, they set all the kids outside, on the steps, so I guess they more or less thought like, with the kids out there, the police would not try to initiate a confrontation…

KR: They probably figured that this government was far too civilized to bomb a house with children inside.

Mr. C: Right. They believed something that they preached against. They preached that the government was violent and they preached that you couldn’t trust them, but then they wound up trusting. They put their kids’ life on the line in trust of the same system that they said they didn’t trust. They contradicted themselves in that aspect.

KR: The wild thing about it is, when [official police] patience does run out [and they  choose to attack] it seems to run out to the extreme. … And even here, you had the situation where they waited and they waited and they waited, Frank Rizzo barricaded them up for a year, tried to starve them out before he assaulted them back in 1978, but it was like, whenever the decision was made that, okay, we’re out of patience, we’re going to make a move, it’s always extreme violence and results in death. Here it was eleven people; in [the ATF assault on the Branch Davidians and David Koresh in] Waco, Texas it was 74; Ruby Ridge, Idaho – Randy Weaver was a racist, he admitted it, he was a White separatist, though it may be different from being a White supremacist – but they killed his 14-year-old son, killed his dog first, and they shot his wife in the face, when she was holding her infant in her arms. … She was shot from a distance of 200 yards.

choose to attack] it seems to run out to the extreme. … And even here, you had the situation where they waited and they waited and they waited, Frank Rizzo barricaded them up for a year, tried to starve them out before he assaulted them back in 1978, but it was like, whenever the decision was made that, okay, we’re out of patience, we’re going to make a move, it’s always extreme violence and results in death. Here it was eleven people; in [the ATF assault on the Branch Davidians and David Koresh in] Waco, Texas it was 74; Ruby Ridge, Idaho – Randy Weaver was a racist, he admitted it, he was a White separatist, though it may be different from being a White supremacist – but they killed his 14-year-old son, killed his dog first, and they shot his wife in the face, when she was holding her infant in her arms. … She was shot from a distance of 200 yards.

Mr. B: We still don’t know what the circumstances might have been, the reason why. Like me, I spent 33 years in the military. We always plan our strategy, what we’re going to do and when we’re going to do it. So you sit down, you make your plans, you get your objectives and everything. And you keep doing it, and then you get to that point where you’re not getting any results. The final moment is coming, and you make your move. And I think this is to say that the city and everything with MOVE, Waco or whatever, after a while patience runs out and you’ll have no more sympathy.

KR: Well, looking at the Weaver situation, from what I’ve read so far, Weaver was acquitted on all the charges except one minor one leading up to the incident, and basically, he was also acquitted of all charges regarding the actions he took during the standoff. So they actually pretty much determined that he was shooting back in self-defense. In Waco, now there was a question as to whether or not the weapons that they had in Waco were really illegal weapons or not, there is some degree of question about the child abuse allegations that had been filed, so a lot of the charges that were leading up to a lot of these confrontations, upon further review, are being either revealed or being considered to possibly have been relatively minor and it makes you say “Well, why did we go through all of this stuff in the first place?” Randy Weaver is in an isolated cabin!

Mr. C: He wasn’t a threat to anybody, and that’s why he won his case – I don’t know if it was so many millions of dollars or so, but he won his case. But the same thing happened with Ramona. She was acquitted [of almost all of the charges against her], she represented herself in her case when she went to jail for inciting a riot. But every other charge they had against her was thrown out because they couldn’t substantiate it. And, the original arrest warrants that they had on the people were never substantiated as far as their validity. So, it was questionable whether Ed Rendell, the former mayor who was the DA at that time, had the proper evidence for Lynne Abraham who is the DA now and was a judge then …

KR: And she wants to see Mumia Abu-Jamal dead. There’s all kinds of connections here!

Political Connections and Cover-Ups?

Mr. C: You see, everybody who was connected with the MOVE case and with Mumia’s case, everybody with maybe the exception of the judge, everybody made progress in their careers. Like the DA who actually held that grand jury there, Ron Castille, he became a judge.

KR: He actually wound up being one of the people who decided that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court would not hear Mumia Abu-Jamal’s appeal, which a lot of people thought was very strange, when you have someone who was trying to convict him back in the 1980’s and now he’s sitting on the Supreme Court saying “We’re not going to review his case!” That’s like Sabo reviewing the appeal of his own conduct!

Mr. C: And that also happened [when] some of us from this block went to the Justice Department to get them to reopen the MOVE case.

Did the people die in the fire or were they shot?

KR: To reopen it?

Mr. C: Yeah, reopen the case, because it was found that there is a forensic pathologist who sent in a report to the MOVE grand jury that the deaths of those 11 people were homicides. There was another pathologist who was brought in to identify the sex and ages of the bodies. He also agreed that the deaths were homicides because they found bullets in several of the MOVE people. Also, they found that at least two heads were missing. From John Africa, I think Conrad Africa’s heads were missing. And saw marks on their necks. [In the] Temple University archives … we saw some of the pictures of the bodies that were fully clothed but were supposed to have burned up in the fire. But they were actually fully clothed. So that led us to believe that they were outside of the house when they were killed.

KR: Do you think they were killed by …?

Mr. C: The only people back there were police.

KR: Because Ramona did say when they tried to leave out of the back of the house they were shot at.

Mr. C: And so did the young boy. Birdie Africa said the same thing.

KR: Of course he turned on MOVE shortly after he got out.

Mr. C: He turned on MOVE but he never changed his story as to what happened that day. So he still says that – and he maybe had a personal problem with MOVE because he was a young man under the influence – but his testimony never changed and it still hasn’t changed today. [“Birdie Africa” would later change his name back to his given name, Michael Ward, and raise a family before dying on a cruise in 2014 – Editor.]

KR: That’s interesting because I don’t even know that the newspaper articles even talk about his testimony that you were just saying.

Mr. C: Well, they discounted his testimony because they said that he was too young.

KR: And he said they were fired upon?

Mr. C: He said they were fired upon. He even recounted what it sounded like. Tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat, like a machine gun, automatic weapons fire. So they both corroborated each other. But what happened was, when the grand jury was convened, and this particular doctor who was sent here to Philadelphia to monitor, to evaluate the Medical Examiner’s office here – the Medical Examiner’s office lost their accreditation at that time because they didn’t handle the autopsies properly – this doctor submitted his information to the DA’s office and they conveniently did not use that information. … The grand jury never heard his report that said that they were homicides. And the only mention of homicide that the grand jury heard was a little excerpt from the doctor who was brought in to tell the sex and ages of the bodies. So, his primary reason for being there was to determine sex and ages. So his focus was not on whether it was homicide or not, but he did put in his report that the deaths were homicides.

KR: Oh, he stuck it in there?

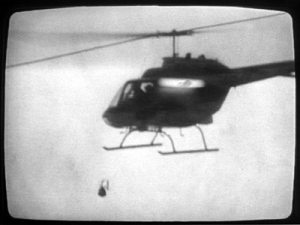

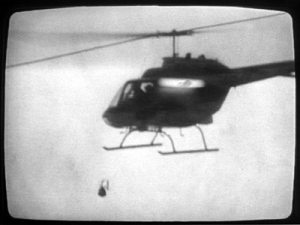

Mr. C: He put it in there, and they said there was no corroboration but they withheld information that [there] was. So it was strange that they withheld this – we didn’t find out about the withheld homicide information until after statute of limitations had run out, which in federal, it’s a five year statute of limitations. Now local it’s not, but federal civil rights violations is five years. So anyway, we went down there and everything, but what we got out of it – they turned us down – but we found out that Richard Thornburgh, who was the attorney general at that time, he had been governor, so when you mention about conflict of interest with Castille maybe, or his motivations being suspect, we had the same situation because the bomb was dropped by a helicopter that was property of the state, and the state governor was Richard Thornburgh. Then he went right to become attorney general, so quite naturally, the people who investigated the civil rights violations here were under his thumb, so he investigated himself!

Mr. A: We were blocked at every turn!

Mr. C: He investigated himself, and like I was talking to one of his assistants in Washington, and he said, really, they got away, he said, with the evidence that came out, it doesn’t matter. He said even if somebody comes out and admit that they did it, statute of limitations has run, so they’re not going to do anything because statute of limitations allowed them to beat it. So the reports were withheld until after that. We went on the fifth anniversary and we didn’t find out until after the fifth anniversary that this information existed. So here you actually have proof of homicide but you know what? No politician, no big-time civil rights advocate, including Johnnie Cochran – because I was in touch with Johnnie Cochran’s office and they were afraid to deal with it, and they passed it off they couldn’t do this, that and the other, so many reasons, but the end result was they couldn’t do it – because this is a situation where, if you are able to put a charge on somebody, you’re talking about a charge of murder. And when you’re talking about a charge of murder, you’re talking about linking these big politicians, not only them, but you’re talking about linking the President of the United States, because the C-4 was released by the FBI, which was the active ingredient in the bomb. And the attorney general at that time was Ed Meese. And he publicly said – I saw it on TV, he said to  Wilson Goode – “Job well done” after everything had happened. Now, I have enough sense to know that the attorney general doesn’t authorize the release of a military bomb to a local police department unless they have a strategy that the President approves of, because he could get fired like that [snaps his fingers] doing something dumb like that. So, I do know from being on the police force, and which I know any of you all who have been in the service [also know], the chain of command is held in strict adherence, and a lot can happen to anybody who violates the chain of command. So anybody who tackles this case would be bringing out the responsibility for these murders by all these big political figures, all the way up to the President. So nobody, at all, ever, no law firm – I talked to a lot of law firms, I talked to a lot of big-time law people in the city and outside the city, and none of them had the courage. I talked to the ACLU and I talked to a lot of people. …

Wilson Goode – “Job well done” after everything had happened. Now, I have enough sense to know that the attorney general doesn’t authorize the release of a military bomb to a local police department unless they have a strategy that the President approves of, because he could get fired like that [snaps his fingers] doing something dumb like that. So, I do know from being on the police force, and which I know any of you all who have been in the service [also know], the chain of command is held in strict adherence, and a lot can happen to anybody who violates the chain of command. So anybody who tackles this case would be bringing out the responsibility for these murders by all these big political figures, all the way up to the President. So nobody, at all, ever, no law firm – I talked to a lot of law firms, I talked to a lot of big-time law people in the city and outside the city, and none of them had the courage. I talked to the ACLU and I talked to a lot of people. …

KR: The ACLU wouldn’t touch it?

Mr. C: The ACLU said they didn’t have the manpower to put on the case for the type of time they would need. So, it’s a murder case here, 11 murders that were swept under the rug, there’s evidence. I even talked to the district attorney on a radio program, Lynne Abraham. And I posed the question about this withholding of evidence to her, and that the evidence existed that there was homicide by this forensic pathologist, and what she did, she assassinated this guy’s character. She said “Well, I wouldn’t believe anything he said because I think he was removed from his position as a medical examiner” in such-and-such a place which was over in Jersey, “and I think he’s such-and-such” so she was saying he was not credible.

KR: She didn’t hire him, he was an independent pathologist?

Mr. C: He was independent, but when I talked with him, he said first of all, he never was removed from any position he ever has held, and he said second of all, she has and was currently using him as an expert witness for the prosecution while she was DA. So if she felt he was not credible, how could she use him for her side? So it was one of those things where some of these people will blatantly lie because if she had accepted that what I said was accurate, that it was homicide, then she would have to explain what transpired. So to avoid that, she just called him a big nothing, you know. So there’s a lot to this case here that has not hit, and the thing about the evidence of homicide, and that the medical examiner didn’t use the proper procedures and all of that, so they could not find the accurate reason why the deaths occurred and they attributed all the deaths to accident, because the fire caused them to die, and the fire was meant to do one thing but, inadvertently, another thing happened.

KR: Meant to blow a hole through the fortified roof and instead burned down the houses.

Mr. C: The bomb meant to blow a hole. The fire meant to drive them out. But instead they’re saying, they stayed in there. They tried to come out, they ran back in, and they just all perished right inside the building.

KR: Whereas instead, they actually ran out and they were shot?

Mr. C: And there was a TV news conference with the mayor, Wilson Goode at that time, and the police commissioner, Sambor at that time, where Sambor actually said that “the MOVE people ran out the house, they were running toward the parkway which is at the corner, they got halfway between the MOVE house and the parkway we’re involved in a gun battle with them right now.” And he said, “I don’t know if anybody was killed so far, but right now we’re involved with a gun battle.” So then he came back later in the same news conference and said, “Uh, excuse me, the alleged gun battle” – and he had just said it was a gun battle – “the alleged gun battle did not occur, and there never was a gun battle between MOVE and the police department.” So now you have him coming up with that. Where did he get this information from in the first place? Then you find out that you have people who were in the house, supposedly found dead in the house, fully clothed, but the house burned down to the ground, the whole three blocks is burned down, and they were inside the house but they were fully clothed. Not even a singe on their clothing.

Mr. A: Tell him where they found all the bodies.

Mr. C: Well they claim they found all the bodies within the MOVE house boundaries, property lines of the MOVE house, but human nature is going to tell people that nobody is going to run into an inferno.

KR: Only a horse runs into a burning barn.

Mr. C: And we’re not horses! So you actually had proof of homicide, based on circumstantial evidence, and the testimony of forensic pathologists, more than once so they can corroborate, all this information was withheld from the grand jury, and no one wanted to reopen the case to bring out, to allow the facts and the other information to come out. So right now it still stands as accidental deaths.

“We will kill you down to a little baby”

Mr. C: Right here they notified the hospitals that they had, like when they took out Birdie Africa and Ramona Africa, sent them to the hospital, they notified them to be ready, they were going to send some more people to the hospital. But then, they said all the people were dead. See what I mean? So the other people never materialized in the first place. So this is symptomatic of the entire country, this type of police operation, and I think what it amounted to was, I think the whole thrust is that the government is trying to scare anybody who may disagree with the government, who wants to protest, scare them to the extent to say “We will kill you down to a little baby.”

KR: And they make an example out of a group like MOVE who, because of the in-your-face, extremely radical way that they communicated their point, they’d be able to turn off a lot of people simply by virtue of their methods….

Mr. C: Well that’s what happened. That’s what happened something like with Hitler and Germany. Some of the well-to-do Jews, my understanding is that they OK’d some of the means and methods of Hitler that were put on the so-called lower-class Jews, and never realizing that it could happen to them, and then when Hitler said, “Okay, instead of just those Jews, now all Jews …” But same thing with MOVE. When it happened here, a lot of people felt like, “Well, they were like, terrible people because of the way they acted,” so a lot of people didn’t have a lot of sympathy for MOVE. But as time unfolded, as time went on and other atrocities unfolded, they found that the police – see, at that time, so much had happened in Powelton Village, but by and large, a lot of people who maybe weren’t grass-roots people, still felt like the police, if they ever did anything to you, it was because you were wrong. So in later years, after the MOVE thing happened, you started having other atrocities happening, here in Philadelphia and around the country, so it evolved to the point that people now recognize that the police are not always right, and they’re not always fair.

KR: Maybe MOVE had a point with a couple of those incidents.

Mr. C: Maybe MOVE was more right than wrong, because a lot of people today feel like no matter what MOVE’s method of protest was, they weren’t killing anybody. They inflicted imposition on us, the neighborhood, residents, but they weren’t killing anybody, so they didn’t deserve to be killed for their actions. Maybe they deserved to go to jail for six months or something like that, or 90 days or something like that, okay? But they didn’t deserve to be gunned down, a bomb dropped on them, we residents didn’t deserve to have them to burn the whole area out.

KR: Sixty-one houses?

Mr. A: Using the flames as a tactical weapon.

Mr. A: Using the flames as a tactical weapon.

KR: And they let it burn for a while.

Mr. A: Absolutely! They let it burn. They used it as a tactical weapon.

Mr. C: They said that there was a bunker on top of the front of the house, and since the bomb didn’t blow the bunker off the roof, they wanted to let the fire burn enough to burn the bunker off.

KR: As skilled as these guys are at imploding a large building without touching any of the properties on either side of it, you’d think they’d be able to exercise something like that with a little more precision.

Mr. C: Right. See, that was their story but we don’t believe that was their goal. Their goal was extermination.

Mr. A: Their intention was to do exactly what they did. That’s what their intention was.

KR: But why would they want the whole neighborhood gone?

Mr. C: Because then the evidence gets lost in the shuffle.

Mr. A: Why? Why? Because we’re Black folk. This isn’t the first time they’ve used the bomb on us. They did it once before in Philadelphia!

Mr. B: But not only that, they knew that John Africa was in there and the majority of the MOVE people were there. So therefore they figured if they could exterminate them and let the fire burn, get rid of MOVE, that would be it. But it failed on them.

KR: Pam Africa was not in there!

Mr. B: Right. Not only that, Ramona and Birdie escaped. But they figured, knowing that he was in there, he was the root of it. If they killed the head…

KR: Of course, they martyred him. Now, was there any sense among the neighbors, as the conflict was going on – because one impression I got after reading about Powelton Village and reading about everything that went before, was that, in many ways, the things that MOVE was doing and the way they were acting was more because of all the stuff that had happened before, whereas earlier on they might have been a little bit purer in their political focus, but as time went on and as their people got beat and as their babies died and as people got thrown in jail for a hundred years, that after a while maybe it affected them psychologically, to the point where now they’re just fixated on their own political prisoners?

Mr. C: Well, they were fixated on their strategy when they were down in Powelton Village, but they became fixated on getting those people who were arrested in Powelton Village out of jail. That’s why they did what they did here on Osage Avenue. They were on a mission from Day One. Because I had talked with them when they were down in Powelton Village. We knew some of them; the mother of one of the members and the sister of the founder lived on the block. So some of us had talked with them and they were on a real mission, but here their primary focus was on getting their people out of jail. And they told us, “We’re going to use you, because if we go out into the wilderness, nobody’s going to listen to us.”

KR: I remember reading that quote. They said “No one’s going to listen to us, so….”

Mr. B: They didn’t have the protection.

Mr. C: So they just believed in something they really said they didn’t believe in, and that was the compassion of the city, the government.

KR: It almost sounds like the difference between the rhetoric and whether they really thought they would do it. They threw the rhetoric out there that these people are snakes, they’re cancerous, they don’t care what they have to do to whom, and yet they still gave them some small credit for being civilized enough to not kill them all.

Racial Politricks

Mr. C: I think that was attributed to the fact that we had a Black mayor. See, because this was our first Black mayor, and I think they really felt that a Black mayor would not allow it to happen. And they didn’t consider that maybe this Black mayor might be constrained by other government, and as we found out, the federal government was involved. So, maybe if they had analyzed it that way, then they wouldn’t have put so much trust in this Black mayor.

KR: Was there any sense here, among the neighbors in general, that MOVE, through their in-your-face actions, was showing up Wilson Goode? I know, for instance, in Baltimore City, I know that there were a number of people who were so much behind Kurt Schmoke, not necessarily because of his record, but because of the fact that he was the first elected Black mayor of Baltimore City, and they didn’t want to see him embarrassed. Was there any sentiment along the lines of, These folk up here are basically making a fool out of the first and maybe the only Black mayor in Philadelphia’s history?

Mr. B: No, I wouldn’t say that. I think what it was, Goode would show more sympathy because they were Black. But, here’s the thing also. If you remember, the police and the fire department, their contract was screwed up, and Goode did not give them what they were looking for in a contract, and it was brought out that the police department and the fire department – especially the police department – had a gripe with Goode. And so therefore, in order to show Goode up, to get even with him, this was Sambor – he was the police commissioner, and to me, he was one of the biggest racists around.

KR: So Sambor, if anyone, was the main person who was trying to show Goode up, to make him look like a fool.

Mr. B: So, this was to disgrace the mayor.

KR: Now, there was one other thing that I had read, that when Wilson Goode was the city manager…

Mr. C: Managing director.

KR: Yes, when he was the managing director. He had implemented a whole lot of things. He’d had a Crisis Intervention Network … supposedly in part as a result of the 1978 confrontation, so he puts this entire network of agencies that are supposed to deal with these kinds of situations, he puts that in place, but then as mayor, he doesn’t use it here.

Mr. C: Well my understanding is, I don’t know what he put in place…

KR: I even heard they de-funded it! I heard Bennie Swans was frustrated because they were getting ready to de-fund the whole thing because they thought they were too activistic in ‘78.

KR: I even heard they de-funded it! I heard Bennie Swans was frustrated because they were getting ready to de-fund the whole thing because they thought they were too activistic in ‘78.

Mr. C: Well, I don’t know what Wilson Goode did as far as initiating crisis intervention or funding it or what have you, but I do know some of the people who were in that crisis intervention and who I saw out here, but at a certain point they were told to discontinue negotiations.

KR: Yeah, they were told to go away.

Mr. C: Right. So, in effect, the use of trained crisis negotiators was taken away. So they had no professional negotiators to attempt a resolution with MOVE after a certain point. Like, in the last days before they had this attack on MOVE, you had some political types to come out.

KR: I’m surprised they didn’t call up Walter Palmer on the Bat-Phone right away, because from what I’ve read, in Powelton Village, he came the closest to actually solving everything. They’d actually come up with an agreement on May 5, 1978. They had an agreement that had MOVE vacating the house, that had them finding another place to live, but supposedly a number of things happened. I think the farm had something to do with it, I think Delbert Africa was concerned that they were either going to be used as slave laborers on the farm or else the farm was surrounded on three sides by a marsh and it was a setup, to get them out of the public eye, to get them away from witnesses, so they could be exterminated. Which was the reason why Geronimo [jiJaga] Pratt, in 1970, fought off the police in L.A. for four hours because he said, “We’re not giving up until the press and the general public are here to see it, because if we surrender you’re going to do the same thing to us that you did to Fred Hampton, which is execute us. So there seemed to be at least some precedent – whether or not MOVE’s concern was rational I don’t know – there seemed to be some precedent for saying “We don’t want to be put in a position where we’re going to be isolated, there’ll be nobody there to see what happens to us.”

Mr. C: That could be also, and probably was, but their strategy said that they should be here because, in order to be heard, they had to be in an urban environment, because if they’re voicing their complaints and they’re out in the wilderness nobody’s going to hear them.

KR: If a tree falls in the forest and nobody hears it, does it make a sound?

Mr. C: Here, they just disrupted our lives, which they told us that was their method, to make us mad enough to go to City Hall, and make City Hall mad enough to come out and try to resolve it. So, I think they had to have it in this type of environment in order to get the result that they wanted. But it just goes to show you that the government found another way to beat a murder rap, so they didn’t care if it was on TV, in an urban environment, right in a little row house block, surrounded by people. They didn’t care. They were still going to commit murder. But the way that they go about beating a case is controlling the evidence.

KR: Just like they bulldozed the Powelton Village house the day after the assault.

Common Oppression, but No Common Philosophy

Mr. B: There’s something. To have a confrontation with the city because you have members in jail and you want them out. You have your confrontation, and where are those members now?

KR: They’re still in jail. They did not succeed.

Mr. A: The best laid plans of mice and men.

Mr. B: They had a bad strategy. In other words, we are members of the same community as MOVE, so we share the same oppression that they share. They had their way to deal with it, we had our way to deal with it, they were different ways. But, no way is good when I’ve got to hurt somebody that I’m on the same side with to get to the person who I’m against. Why should I go against my own brother to try to get to somebody over this? That’s what they, in fact, did to us. They stepped on us to get to the city.

KR: Do you think a coalition could have been made…

Mr. C: No. Us and them?

KR: From the beginning, if, maybe, some of the things that had been done hadn’t been done?

Mr. C: No. Because they were fixated with John Africa’s strategy. And so we could never have compromised a direction … and come to agreement on a strategy that we could agree to because it was either their way or no way. You see what I mean? So, we didn’t have a choice because we couldn’t subscribe to what they were going to do, and they didn’t have a choice because they couldn’t subscribe to what we were going to do.

KR: So, it’s almost like a “lose-lose” situation, then?

Mr. C: Well, that’s what happened.

Mr. B: Like I said, it was a bad strategy, eleven lives lost, and the members are still in jail.

Mr. D: What I still can’t understand, is why they kept the kids in the house.

Mr. C: Because they felt like Wilson Goode had compassion and authority.

KR: Some people would say it was the same reason that Dr. King had children in the marches in Birmingham, Alabama. There were children in those marches. There were men, women and children who were marching peacefully through the streets, and they were getting hosed, and they were getting attacked by dogs.

Mr. A: And MOVE didn’t learn anything from that, because it didn’t work then and it wasn’t going to work for them. They got more than what they really bargained for. They never imagined, they never imagined. …

Was MOVE as “Dangerous” as the Hype?

KR: I’ve heard claims that MOVE’s weapons were inoperative. Was there anything behind that?

Mr. C: Well, they only had a couple of weapons in the first place. I think they had a revolver, a shotgun and a rifle or something like that. They only had two or three. And I don’t know if they were inoperable or not, but it was never proven – and this is what the whole thing was based on, the attack was based on this – the attack was based on that MOVE people shot at the police, and that the police retaliated.

KR: In Chicago, they tried to say the same thing about Fred Hampton. Never any evidence that bullets came out of Fred Hampton’s house.

Mr. B: I don’t know who fired first. My wife and I were sitting right there at 63rd and Spruce when the first rounds were fired, then the “pinging” and bullets flying across the parkway, and it scared me so, I’m sitting right there, I’m trying to start the car to get out of the way, the door flies open, I’m about to fall out of the car, you know what I mean? And the cops are running, and one thing that was happening…one police officer was down, they dragged him down Pine Street, they threw him into an emergency vehicle. We never heard anything else about it.

Mr. C: And see, they also brought somebody out of the park down here. And nobody ever heard anything about it. A lot of strange things that happened with this whole thing, because at one time it was thought that the MOVE people had dug and tied into the sewer system.

KR: And they supposedly planted explosives [a rumor that was never supported by any evidence] in the neighborhood too. Did anybody really buy into that?

Mr. C: Well, we weren’t sure. Because we know that they had gas cans up on the roof. And we know they were in a state of mind where we couldn’t be sure what they would do or what they wouldn’t do. So we felt like it was a possibility because we felt like, maybe, if the police came in and they got to a certain point where they might detonate something around here–we didn’t know–it was hard for us to know what they would do.

Mr. A: They moved a lot of dirt out of there. It was kind of deep. It was interesting watching them build the bunkers on the houses, and watching the police sit up there and watch them build the bunkers. …

Mr. C: Well I hope you got something for your report.

The MOVE Nine after the 1978 assault.

KR: I expected it to be a very positive and eye-opening thing for me, because, basically, the impression that was given by what I’ve read and what I’ve seen was that Powelton Village was an integrated community where they didn’t like Frank Rizzo, so they were kind of supportive of MOVE. Osage Avenue was a Black community they were supportive of Wilson Goode and they didn’t like the fact that Wilson Goode was being made a fool of by MOVE so Osage Avenue was nowhere near as tolerant of what was going on with MOVE as Powelton Village was. And I’m coming to see that that’s really a ridiculously simplistic analysis of the whole situation. I mean, there’s a whole lot more going on there than who the mayor was and what the racial makeup of the community was. It would seem to me, more than anything else, it was more the fact that by the time MOVE got here, their whole attitude had been ratcheted up several times. I mean, however freaked out they were in Powelton Village, I’m thinking that, if I’m freaked out in Powelton Village and the official response is to assault my house, convict nine people of shooting one bullet into one police officer [James Ramp] when they don’t even know what gun it came from, they don’t know what direction it came from, they don’t know if it was friendly fire or not….

Mr. C: But see, the thing is, they do know. They know the bullet came from behind…

KR: They know that?

Mr. C: That was a fact proved by the medical examiner.

KR: They know that the wound in the front of his neck was an exit wound?

Mr. C: Right.

KR: Did they know he was rushing the house at the time?

Mr. C: Well, I don’t know, I don’t know that. But I do know that the trajectory was inconsistent with where MOVE was located, so MOVE couldn’t have fired it.

KR: Okay. I’ve heard that contention, but only from MOVE. First time I’ve heard it from somebody other than MOVE.

Mr. C: Well that was a known fact, and that’s why MOVE was protesting so vehemently about it, because they said “There’s no way we could have killed him. We didn’t even fire any weapons.”

KR: And then nine people get nailed for one bullet.

Mr. C: But the law is that if you participate in an act that causes a death then you’re as guilty as the shooter.