This Wednesday, June 19th marks the observance of Juneteenth, a holiday that is virtually unknown outside the Afrikan-American community and, perhaps, not that well known within it. On this commemoration, we will include excerpts from a few articles explaining the holiday.

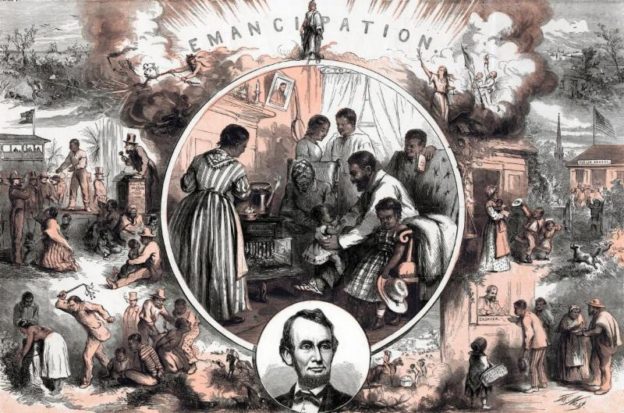

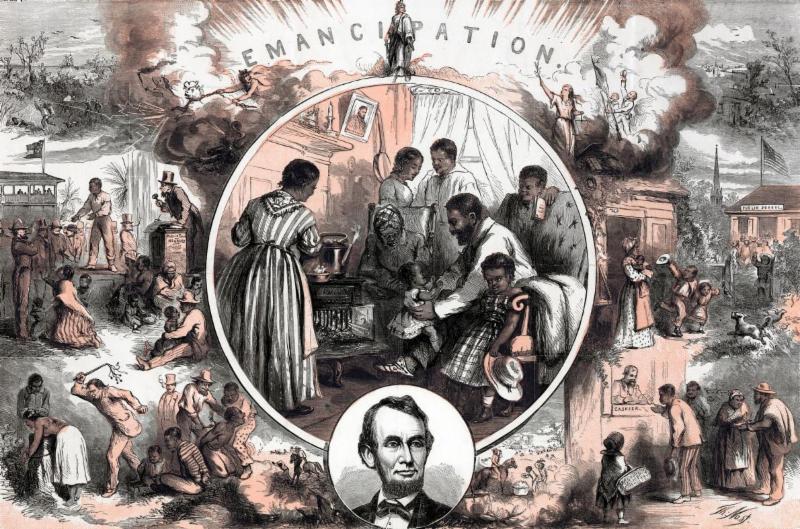

Illustrator and war correspondent Thomas Nast depicted the emancipation of Southern enslaved people at the end of the American Civil War. (from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/holidays/reference/juneteenth/)

The web site www.juneteenth.com includes articles on the history of Juneteenth, information on Juneteenth celebrations across the United States and around the world, and links for interested persons to donate to the site. Here is a brief passage from their article The History of Juneteenth:

Juneteenth is the oldest known celebration commemorating the ending of slavery in the United States. Dating back to 1865, it was on June 19th that the Union soldiers, led by Major General Gordon Granger, landed at Galveston, Texas with news that the war had ended and that the enslaved were now free. Note that this was two and a half years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation – which had become official January 1, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation had little impact on the Texans due to the minimal number of Union troops to enforce the new Executive Order. However, with the surrender of General Lee in April of 1865, and the arrival of General Granger’s regiment, the forces were finally strong enough to influence and overcome the resistance.

Later attempts to explain this two and a half year delay in the receipt of this important news have yielded several versions that have been handed down through the years. Often told is the story of a messenger who was murdered on his way to Texas with the news of freedom. Another, is that the news was deliberately withheld by the enslavers to maintain the labor force on the plantations. And still another, is that federal troops actually waited for the slave owners to reap the benefits of one last cotton harvest before going to Texas to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation. All of which, or neither of these version could be true. Certainly, for some, President Lincoln’s authority over the rebellious states was in question For whatever the reasons, conditions in Texas remained status quo well beyond what was statutory.

The American and Juneteenth flags.

Wikipedia, self-billed as “the free encyclopedia” on the Web, has an article on Juneteenth, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juneteenth:

During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, with an effective date of January 1, 1863. It declared that all enslaved persons in the Confederate States of America in rebellion and not in Union hands were to be freed. This excluded the five states known later as border states, which were the four “slave states” not in rebellion – Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri – and those counties of Virginia soon to form the state of West Virginia, and also the three zones under Union occupation: the state of Tennessee, lower Louisiana, and Southeast Virginia.

More isolated geographically, Texas was not a battleground, and thus the people held there as slaves were not affected by the Emancipation Proclamation unless they escaped. Planters and other slaveholders had migrated into Texas from eastern states to escape the fighting, and many brought enslaved people with them, increasing by the thousands the enslaved population in the state at the end of the Civil War. Although most enslaved people lived in rural areas, more than 1,000 resided in both Galveston and Houston by 1860, with several hundred in other large towns. By 1865, there were an estimated 250,000 enslaved people in Texas.

The news of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9 reached Texas later in the month. The Army of the Trans-Mississippi did not surrender until June 2. On June 18, Union Army General Gordon Granger arrived at Galveston Island with 2,000 federal troops to occupy Texas on behalf of the federal government. The following day, standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Granger read aloud the contents of “General Order No. 3”, announcing the total emancipation of those held as slaves:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

Formerly enslaved people in Galveston rejoiced in the streets after the announcement, although in the years afterward many struggled to work through the changes against resistance of whites. The following year, freedmen organized the first of what became the annual celebration of Juneteenth in Texas. In some cities African-Americans were barred from using public parks because of state-sponsored segregation of facilities. Across parts of Texas, freed people pooled their funds to purchase land to hold their celebrations, such as Houston’s Emancipation Park, Mexia’s Booker T. Washington Park, and Emancipation Park in Austin.

Although the date is sometimes referred to as the “traditional end of slavery in Texas” it was given legal status in a series of Texas Supreme Court decisions between 1868 and 1874. …

Since the 1980s and 1990s, the holiday has been more widely celebrated among African-American communities. In 1994 a group of community leaders gathered at Christian Unity Baptist Church in New Orleans, Louisiana to work for greater national celebration of Juneteenth. Expatriates have celebrated it in cities abroad, such as Paris. Some US military bases in other countries sponsor celebrations, in addition to those of private groups.

Although the holiday is still mostly unknown outside African-American communities, it has gained mainstream awareness through depictions in entertainment media, such as episodes of TV series Atlanta (2016) and Black-ish (2017), the latter of which featured musical numbers about the holiday by Aloe Blacc, The Roots, and Fonzworth Bentley.

The article “5 facts about Juneteenth, which marks the last day of slavery” on the Web site of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (https://www.ajc.com/lifestyles/facts-about-juneteenth-which-marks-the-last-day-slavery/7c6hmnKk2IRO7grn5bmsJI/), tackles what are perhaps the most misunderstood aspects of this holiday.

The Atlanta-based organization Justice Initiative (hmcgray@earthlink.net), which releases regular commentaries that have been featured in this Web site, shared a commentary by National Geographic’s Sidney Combs, which also reviews the history and significance of Juneteenth (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/holidays/reference/juneteenth/):

What is Juneteenth-and what does it celebrate?

A day remembering the end of slavery in Texas has spread across the whole U.S., with a larger meaning.

By Sydney Combs

June 19, 2019

National Geographic

Known to some as the country’s “second Independence Day,” June 19-often called Juneteenth-celebrates the freedom of enslaved people in the United States at the end of the Civil War.

Freedom after the Confederacy

At the stroke of midnight on January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation came into effect and declared enslaved people in the Confederacy free-on the condition that the Union won the war. The proclamation turned the war into a fight for freedom and by the end of the war 200,000 black soldiers had joined the fight, spreading news of freedom as they fought their way through the South.

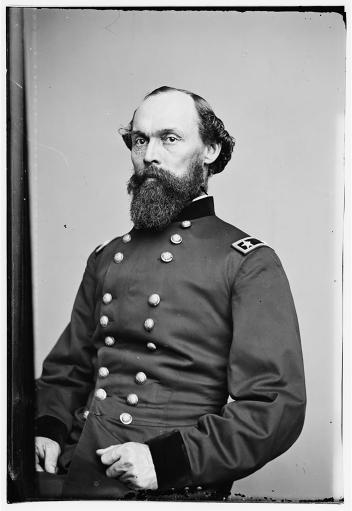

Union leader Gordon Granger told the 250,000 enslaved people of Texas that they were free. PHOTOGRAPH BY LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS & PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION/CIVIL WAR PHOTOGRAPHS

For enslaved people in Texas, emancipation would be a long-time coming. Texas was part of the last stronghold of the South, and without modern communication, it continued to fight after the Confederacy had lost. On May 13, 1865-fully one month after the Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union leader Ulysses S. Grant-the last battle of the war was fought near Brownsville, Texas. News about the Union’s victory slowly spread and within about a month, the last major Confederate army surrendered in Galveston, Texas.

Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston on June 19, 1865 and extended the Emancipation Proclamation to the 250,000 remaining enslaved people in the state-two months after President Lincoln was assassinated. (Explore the Underground Railroad’s ‘great central depot’ in New York.)

On that day, Granger declared, “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

A celebratory day

With Granger’s order, June 19-which would eventually come to be known as Juneteenth-became a day to celebrate the end of slavery in Texas. As newly freed Texans began moving to neighboring states, Juneteenth celebrations spread across the South and beyond.

In 1980, Texas became the first state to recognize June 19 as a state holiday, which it did with legislation. Today, Juneteenth is recognized by nearly every state, and there is an effort underway for federal recognition.

Initial Juneteenth celebrations included church services, public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, and social events like rodeos and dances. As the Civil Rights movement gained momentum in the ’60s, Juneteenth celebrations faded. (Learn how to cook Juneteenth cookies.)

In recent years, however, Juneteenth is regaining popularity and is often celebrated with food and community. It also has helped raise awareness about ongoing issues facing the African-American community, including a political fight for reparations, or compensation, to the descendants of victims of slavery.

For decades, many southern black communities were forced to celebrate Juneteenth on the outskirts of town due to racism and Jim Crow laws. To ensure they had a safe place to gather, Juneteenth groups would often collectively purchase plots of land in the city on which to celebrate. These parks were commonly named Emancipation Parks, many of which still exist today.

Other emancipation celebrations

Despite the holiday’s resurgence in popularity, Juneteenth is still not universally known and is often confused with Emancipation Day, which is annually celebrated on April 16.

Just as Juneteenth originally celebrated freedom in Texas, Emancipation Day specifically marks the day when President Lincoln freed some 3,000 enslaved people in Washington, D.C.– a full eight months before the Emancipation Proclamation and nearly three years before those in Texas would be freed.

Currently, all but four US states (Hawaii, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana) celebrate Juneteenth as a holiday (https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/19/us/juneteenth-state-holidays-trnd/index.html). Pennsylvania became the 46th state (along with the District of Columbia) to officially commemorate Juneteenth on Wednesday, June 19, 2019 when Governor Tom Wolf signed a bill recognizing the holiday. Texas was the first to recognize Juneteenth as a state holiday in 1980.

Pennsylvania governor Wolf signs a bill recognizing Juneteenth in the state on June 19, 2019.

In the Shadow of Juneteenth

This is certainly a day which receives little of the attention it deserves, not so much because of the act of magnanimity of ordering the release of enslaved Afrikans in the United States, but more as a testament to the endurance of a people to resist bondage until, at last, freedom was won. The fact remains that Lincoln needed to free the enslaved Afrikans, if for no other reason than to weaken the Confederate states by taking away their slave labor force, and by enticing those newly-freed Afrikans to join in the Union cause during the Civil War. And the slave revolts, though they were all put down by the combined strength of the United States military, had not stopped, and were not bound to stop. Nat Turner’s 1831 Rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia had struck unprecedented fear into the hearts of slaveowners, and the 1811 Slave Revolt in Louisiana, led by Charles Deslondes, swept through seven plantations on the way to New Orleans and very nearly won the day and, in the words of historian Leon Waters of New Orleans, “could have defeated slavery at one stroke.”

Lincoln, though he was against the enslavement of Afrikans and became known and loved by many Black people as The Great Emancipator (a status that modern-day Republicans never hesitate to throw in our faces as they claim themselves to be “the party of Lincoln” in a vain effort to win our unquestioning allegiance), had never intimated that he believed in the equality of Black people, as he had made clear in his seven debates with Stephen A. Douglas as they contested Douglas’ Illinois Senate seat in 1858; only that he believed our Ancestors deserved the right to live free. Still, Lincoln’s often-stated opposition to slavery and his signing of the Emancipation Proclamation earned him a rather favored position among US presidents with people of Afrikan descent.

We must never delude ourselves into forgetting that there are those who would prefer that we were returned to the place of full servitude and bondage we knew in 1862, as if the Emancipation Proclamation and Juneteenth had never happened.

Contrast this with the current president, Donald J. Trump, who has, during his first two years in the White House, demonized immigrants from Mexico, denigrated Afrikan nations as “shithole countries”, castigated Haitians by intimating that they “all have AIDS”, claimed Nigerians would “never go back to their huts” after enjoying American technology, insisted former president Barack Obama was not an American citizen, denied critical relief aid to Puerto Rico while calling its mayor, Carmen Yulin Cruz, “nasty”, used the same insult against Duchess of Sussex Meghan Markle, refused to recant his call for the execution of the Central Park Five even after their convictions were emphatically reversed (https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/trump-wont-back-down-on-central-park-jogger-case/ar-AACLBeH?ocid=spartanntp), backed brutal police when they have been credibly accused of assaulting unarmed Black motorists and suspects, and any number of other depredations against Afrikan people.

Let us not ignore the news reports from this week of Juneteenth alone, which brings us the continued fight for Reparations on the floor of the United States House of Representatives, in which author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates was forced to take down Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell by reminding him that Reparations are not only owed for what happened to Afrikan people before he was born, but for what has continued to happen to Afrikan people during McConnell’s lifetime, and indeed, for what has continued to happen to Black people under McConnell’s watch.

Let us not ignore the reports of police misconduct that continue to plague this country. First, there was the reprehensible conduct of the Phoenix Police Department’s officers who drew weapons and screamed at a pregnant mother and her child because of a report that the child had shoplifted a doll from a Dollar Store, an incident that brings back stories, for those of us who remember them, of boys being shot in the back for stealing a loaf of bread from a corner store. Next, we hear of the article from CBS Philadelphia, 72 Philadelphia Police Officers On Administrative Duty Over Alleged Racist And Violent Social Media Posts, Commissioner Says (https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/72-philadelphia-police-officers-on-administrative-duty-over-alleged-racist-and-violent-social-media-posts-commissioner-says/ar-AAD7ZZr?ocid=spartanntp). Emancipation may have come 156 years ago, but as former Political Prisoner Marshall “Eddie” Conway has said, “You’re not really free; you’re just loose.”

As we celebrate this day, let us not forget that, as many activists claim, “we are at war”, or perhaps more accurately, “war is upon us.” For we are not truly “at war” until we organize among ourselves to fight for our liberty, unity and uplift as Afrikan people. We must never delude ourselves into forgetting that there are those who would prefer that we were returned to the place of full servitude and bondage we knew in 1862, as if the Emancipation Proclamation and Juneteenth had never happened.