Africa Policy Forum on Famine

Tuesday, April 4, 2017, 8:30 AM

US Capitol Visitors Center

Washington, DC

Congress Member Karen Bass (Democrat from Southern California) holds regular Africa Policy Forum events during the Congressional Session. At these events, experts in various fields important to the uplift of Afrika are assembled to discuss issues from war to famine to economic development. Often, these events seem to reflect more of an “official Washington” viewpoint on US-Africa issues, but the access granted to regular citizens to these events creates opportunities for Pan-Afrikan activists to learn about the efforts to deal with crises on the Continent as well as the plans of business and governmental players to promote US, capitalist and other Western policies in Afrika that may or may not serve Afrikan interests. At the very least, when one attends these events, an opportunity comes later in the discussion to participate in the question-and-answer session (the “Q & A”), which allows one to prepare and ask the occasional Impudent Question. Often, the Impudent Question goes unanswered, but sometimes it gives the participants an opportunity to demonstrate their depth of understanding of the current and historical issues impacting upon Afrika and Afrikan People.

On Tuesday, April 4, forty-nine years to the day after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., one of the most prominent members of the Historical Afrikan Diaspora (descendants of Afrikans who had been captured from Afrika and kidnapped into slavery in the United States and around the world) in history, an Africa Policy Forum on Famine was held. This was the second such Forum of the year; the Forum on Doing Business with the US for Africa, held February 28, may be the subject of a brief article in the near future.

The Forum Panelists

The Forum featured the following speakers [with information from the Africa Policy Forum Biographies of Participants]:

Dr. Monde Muyangwa

Director, Africa Program, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

At the Wilson Center, Dr. Muyangwa leads programs that analyze and offer practical, actionable policy options addressing some of Africa’s most critical issues. Previously, she served as Academic Dean and Professor of Civil-Military Relations at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. She served as Director of Research and Vice President for Research and Policy at the National Summit on Africa, and Director of International Education Programs at New Mexico Highlands University. She serves on the Board of Trustees at Freedom House, and previously was an advisory Council member of the Ibrahim Index of African Governance. She holds a Ph.D. in International Relations and a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from the University of Oxford, and a Bachelor of Arts in Public Administration and Economics from the University of Zambia. She was a Rhodes Scholar, a Wingate Scholar, and the University of Zambia Valedictory Speaker for her class.

General William E. “Kip” Ward

President, Sentel Corporation

Former Commander of the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM)

A retired Army General Officer, General Ward was the inaugural Commander of the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM), where he successfully established the nation’s newest and uniquely positioned interagency geographic command responsible for for all US defense and security activities on the African Continent and its Island Nations with staff representatives from State, Commerce, Treasury, Homeland Security and other US Cabinet Departments and Agencies. Prior to commanding AFRICOM where his visionary leadership promoted the value of forging relationships, creating partnerships, enhancing regional cooperation and the importance of sustained security engagement in pursuing US national interests, he was the Deputy Commander, United States European Command, responsible for the Command’s day-to-day activities.

He is a decorated combat veteran and holds a B.A. Degree in Political Science from Morgan State University in Baltimore and a Master of Arts Degree in Political Science from the Pennsylvania State University. A Master Paratrooper, he is a graduate of the Infantry Officer Basic and Advanced courses, Fort Benning, Georgia, the US Army Command and General Staff College, Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, and the US Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. General Ward was an assistant professor, Department of Social Sciences, teaching political science and public policy at the United States Military Academy, West Point.

Selected by then-US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to serve as the United States Security Coordinator, Israel-Palestinian Authority in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, General Ward was praised by Democrats and Republicans for bringing a degree of fairness and equity to his work. He has held other Army, Joint and Combined command and staff assignments over a 40-plus year career including NATO Force Commander in Bosnia, Commander 25th Infantry Division and Vice Director for Operations, J-3, The Joint Staff, during the September 2001 terror attacks. In the Pentagon, he was at the center of determining and carrying out the US government’s defense and interagency response actions to the attack. He has commanded every level from platoon as a Lieutenant to geographic command as a General.

John Prendergast

Founding Director, the Enough Project and Co-Founder, The Sentry

Mr. Prendergast is a human rights activist and New York Times best-selling author who has focused on peace in Africa for over thirty years. He is the Founding Director of the Enough Project, an initiative to end genocide and crimes against humanity. With actor George Clooney, he also founded The Sentry, a new investigative initiative focused on dismantling the networks financing conflict and atrocities. He has worked for the Clinton White House, the State Department, two Members of Congress, the National Intelligence Council, UNICEF, Human Rights Watch, the International Crisis Group, and the US Institute of Peace. He has been a Big Brother for three decades, as well as a youth counselor and a basketball coach. He is the author or co-author of ten books. He also co-founded the Satellite Sentinel Project, which used satellite imagery to spotlight mass atrocities. With several NBA stars, he launched the Darfur Dream Team Sister Schools Program to fund schools in Darfuri refugee camps. He also created Enough’s Raise Hope for Congo Campaign, highlighting the issue of conflict minerals, and its student arm the Conflict-Free Campus Initiative. He also runs Not On Our Watch, the organization founded by actor-activists Matt Damon, Don Cheadle, Brad Pitt and George Clooney. Mr. Prendergast has been awarded six honorary doctorates. He has been a visiting professor at Yale Law School, Stanford University, Columbia University, Dartmouth College, Duke University, and others. He has appeared in five episodes of 60 Minutes, for which the team won an Emmy award, and helped create African stories for two episodes of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit. He has also traveled to Africa with NBC’s Dateline, ABC’s Nightline, PBS’s NewsHour, CNN’s Inside Africa, and news outlets and magazines Newsweek and The Daily Beast. He also appears in the motion picture “The Good Lie”, starring Reese Witherspoon and Emmanuel Jai, as well as documentaries including Merci Congo, When Elephants Fight, Blood in the Mobile, Sand and Sorrow, Darfur Now, 3 Points and War Child.

Jon C. Brause

Director, Washington Office, United Nations World Food Programme (WFP)

Jon Brause is the Director of the Washington Office of the UN World Food Programme (WFP). In this role, he oversees WFP’s relationships with its major partners in the US government and represents WFP in dialog with US-based organizations interested in reducing hunger and poverty worldwide. He came to WFP after 22-year career at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), where he served as the Deputy Assistant Administrator in the Bureau for Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance. He has also served as the Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Relief, Stabilization, and Development in the National Security Council, and as the Director of the Office of Program, Policy and Management at USAID. As Senior Policy Advisor to USAID Administrator Andrew S. Natsios, Mr. Brause monitored humanitarian and developmental policy with a focus on Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean. During his tenure in the Office of Food for Peace, Mr. Brause managed all aspects of US government food aid programming for humanitarian activities worldwide.

The Africa Policy Forum on Famine

We include here most of the full transcript of the discussion (to the degree that we were able to successfully transcribe all of the comments), with some of the points of the speakers highlighted for emphasis. The full comments of all the speakers will give an idea of their individual perspectives, however. For example, General Ward, though he has had a distinguished career in military security, regularly spoke of the need for development as well as security based on his experience in northern Nigeria with AFRICOM. Mr. Brause spoke much about the impact of the raw numbers of people at risk and seemed focused on ways to bring relief to suffering populations. And Mr. Prendergast seemed keenly aware of how the legacy of colonialism and exploitation of Afrika, by corrupt leaders, neo-colonial interests and international opportunists such as weapons manufacturers and money-launderers, had escaped much-deserved culpability for the current state of affairs in Afrika’s crisis zones. Meanwhile, Dr. Muyangwa was working the entire time to maintain control of the flow of conversation to ensure everyone had an opportunity to ask questions, and gave an in-depth summary of the discussion at the end of the event. All of them acknowledged that it is the Afrikan people in the affected countries that are actually taking the lead in responding to the crisis, even as the international community seems to be often falling down on the job.

CONGRESS MEMBER KAREN BASS:

Good morning everyone. I’m Congresswoman Karen Bass. I want to welcome everyone here for the second Africa Policy Forum that we’ve had this year. Normally when we have these Forums we’ve focused on looking at business and economic opportunities and how to promote US-Africa relations but this time we’re gathered for a topic that has become of increasing concern. This is a critical topic in that it has been said in the United Nations that we have potentially the worst humanitarian crisis since the United Nations was founded. The potential of 20 million people facing famine in four countries. Today we’re going to talk about three of the countries, the countries on the Continent, which is not to ignore  Yemen, but we are going to focus on the African Continent today. And this is with the backdrop of a new Administration that is suggesting a 30% cut in foreign assistance. I would think that, at this point in time, where we have the opportunity to prevent a horrible tragedy, we know that famine has already been declared in South Sudan, but it could obviously get far worse, but we have an opportunity for our country to step up like we did in the Ebola Crisis and rally the entire world, but unfortunately at this point in time, we seem to be going in the opposite direction. I will tell you though, that from the point of view of Congress, last week we had a hearing in the House of Representatives of the full Foreign Affairs Committee, and Democrats and Republicans were both united in a concern that you can’t cut a foreign assistance budget by 30%. Later today there will be a meeting amongst Democrats to discuss the famine, and it seems to me that the most critical thing that we could be doing at this point in time is to raise public awareness and public outcry at the beginning, before this crisis really expands. So that is our topic today, and before I introduce our moderator, I would like to call up one of the leaders in the Democratic Caucus, one of the leaders in the House of Representatives, someone who everyone knows, who led the fight around HIV. please welcome Congresswoman Barbara Lee.

Yemen, but we are going to focus on the African Continent today. And this is with the backdrop of a new Administration that is suggesting a 30% cut in foreign assistance. I would think that, at this point in time, where we have the opportunity to prevent a horrible tragedy, we know that famine has already been declared in South Sudan, but it could obviously get far worse, but we have an opportunity for our country to step up like we did in the Ebola Crisis and rally the entire world, but unfortunately at this point in time, we seem to be going in the opposite direction. I will tell you though, that from the point of view of Congress, last week we had a hearing in the House of Representatives of the full Foreign Affairs Committee, and Democrats and Republicans were both united in a concern that you can’t cut a foreign assistance budget by 30%. Later today there will be a meeting amongst Democrats to discuss the famine, and it seems to me that the most critical thing that we could be doing at this point in time is to raise public awareness and public outcry at the beginning, before this crisis really expands. So that is our topic today, and before I introduce our moderator, I would like to call up one of the leaders in the Democratic Caucus, one of the leaders in the House of Representatives, someone who everyone knows, who led the fight around HIV. please welcome Congresswoman Barbara Lee.

CONGRESS MEMBER BARBARA LEE:

Well, good morning. First of all, let me thank our ranking member, Congresswoman Karen Bass, for doing such a phenomenal job, on so many issues, such as relates to the continent. Whether it’s training, whether it’s foreign assistance, whether it’s health care, education, whether it’s the AU, whether it’s the United Nations, she has been on point on each and every issue, and so I want to thank her for continuing to beat the drum to make sure that Africa is a priority in our foreign policy. We thank all of our panelists for being here, and thank you for your vigilance, for your expertise and for sharing with us what you know, but also what we need to do, and finally I’ll just say I’m on the Subcommittee on the Appropriations Committee which funds our foreign assistance, and Congresswoman Bass, and Meeks, myself, and also Republicans, we have forwarded a letter to the Appropriations Committee for emergency funding for the famine, and we’ll see where that goes, but believe you me, we are working right now to make sure that we target resources so that we can mitigate against so many people dying of starvation. So thank you again and thanks so much for your continuing support for the Continent and for your expertise and for being here, for supporting Congresswoman Karen Bass because these forums are extremely important in terms of public awareness and in terms of giving us strategies on where we need to go as Members of Congress. Thank you again.

CONGRESS MEMBER KAREN BASS:

We’re very lucky to have Barbara Lee sit on the Foreign Ops Committee, as she mentioned, that’s Appropriations. She’s got the purse strings and knowing that somebody of that leadership has the purse strings, I think we’re in a good position. We also are circulating a letter amongst Members of Congress, to emphasize the significance of the funding. So we’re going to begin our program now, and I’d like to introduce our Moderator for the morning, Dr. Monde Muyangwa, the Director of the Africa Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, and I might mention that, in that budget, the Wilson Center was actually zeroed out. So, one of many issues that we will push back hard on to make sure that does not happen.

General Discussions of the Crisis

DR. MONDE MUYANGWA:

Good morning everyone. I want to thank Congress Member Bass for focusing on this very important issue. It’s been neglected for quite a while now, so it’s good to see that we’re finally paying some attention to this issue. And as you mentioned, what we hope to get out of the discussion this morning is increased awareness of the crisis. But also, a better understanding of the problem, its nature, its scope, the causes and drivers of the crisis, government and other measures in response to the crisis, and what can be done in the short term to address the famine and to save lives and in the long term to better ensure food security and avert recurring drought and famine.

We have three excellent speakers for this morning. I’ll introduce them very briefly. Our first speaker will be Mr. Jon Brause, who is the director of the World Food Programme, the Washington Liaison Office. He will be followed by General William “Kip” Ward, who is the C.O.O. and President of Sentel Corporation, who will speak to us about Northeast Nigeria. And he will be followed by Jon Prendergast, who is the Founding Director of Enough, who will speak to us on South Sudan. We have asked each of our speakers to offer initial remarks of about five to six minutes. Our kickoff speaker will be Mr. Jon Brause, who we’ve asked to give an overview of the crisis and to touch a little bit on Somalia. Mr. Brause, your five minutes start now.

“So how is it now, less than 2 years after the world ratified the Sustainable Development Goals, that we have, in fact, the largest crisis since World War II, and maybe the largest humanitarian crisis in the last hundred years?”

–Jon Brause, World Food Programme

JON BRAUSE:

Thank you. Thanks to Congresswoman Bass and Congresswoman Lee for their welcome and it’s a great pleasure to be here and to have the World Food Programme be able to speak to you today. Just a little bit of background; the World Food Programme was founded on the vision of presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy. And they had a vision after World War II that the world needed help to be stabilized in areas that were struggling through weather related problems or other crises. They knew that the United States and other countries had the capacity to help out. So just as my founding comment, think that that was the vision back just after World War II. And then I’ll take you to 2015 in September when the international community got together and finalized and ratified the Sustainable Development Goals, and those were the goals that stated ‘we can end poverty, we can end hunger, we can educate every child’. These were all things that the world said we could do in 2015; we have the capabilities, we just need the will to get it done. And that was that we could do those things by 2030.

So how is it now, less than 2 years after the world ratified the Sustainable Development Goals, that we have, in fact, the largest crisis since World War II, and maybe the largest humanitarian crisis in the last hundred years? We have over a hundred million people who are going to need emergency food assistance this year. We have 60 to 70 million people who are displaced, either internally or refugees in other countries. And as the Congresswoman said, we have 20 million people in the world today who are facing famine. In four countries. Three in Africa, South Sudan, Somalia and Nigeria, and then of course there’s Yemen. But that 20 million people, you have to put it in perspective. That is more than the number of people in the state of Virginia, and the state of Maryland, and the District of Columbia combined. Plenty more than that. So it’s a huge number of people who are at risk, and we need to start to take action to do something about it.

So then the issue is, what is famine? Why do we need a declaration of famine? Well, famine is actually a very late statement. It means that we’ve missed the boat to a certain extent. People have already started dying. And the criteria technicians use, if you will, to determine when a famine is taking place are three. Two people out of every 10,000 are dying every day. That’s one criterion. More than 30% of the children under 5 are suffering from acute malnutrition. And then the third is that 20% of the households in any region are extremely food insecure, short of food and at risk of starvation. So just to put that two deaths in 10,000 every day into perspective, if your kids go to a high school in Maryland or Virginia, the average population or student body is about 2,500 kids. So that means, in that school, if it were having a famine, that one child, one student, every two days, would be dying. So your kid would be coming home and saying ‘Billy died today’. And then two days later, another child would die. It’s a massive number of people. Don’t let two in 10,000 throw you that it’s some abstract, it’s a real tangible number of people dying every day. And of course, it’s not just food. We have to be very clear that food is very important but if you don’t have clean water, if you don’t have medical care, if you don’t have sanitation facilities, disease will actually overtake hunger. The people will die not from hunger necessarily but from vulnerability to disease. So it will take on many different faces and it’s not just one of food.

“So how did we get here? Why are we now facing this crisis? Well, I have to say, to some extent, we watched it happen.”

–Jon Brause, World Food Programme

So how did we get here? Why are we now facing this crisis? Well, I have to say, to some extent, we watched it happen. Last year, and John will probably talk about this, South Sudan was on the brink of a famine, but it wasn’t declared. But it was terrible. The situation was horrific even last year. In Somalia, they’ve had three consecutive years of bad rains, so even though their governance has improved — and it’s one of the points we want to make, where there is governance, you have a much better chance of addressing the root causes of famine — but Somalia’s had three consecutive years of bad rain, so in may of the cases, in all of the cases, weather is a factor. But unfortunately, the big driver for all of these famines is conflict. And the difference for conflict, a drought will disrupt productivity, everybody can understand that, but if you’re not suffering from conflict, if it’s just a drought, then there are means for the international community, for the governments to engage and to help the people who are in the drought affected areas. In the case of conflict, everything is disrupted. Markets are disrupted, agriculture is [disrupted], trade is interrupted, jobs and livelihoods are all interrupted. So the whole system fails. And in the case of three of the countries, Nigeria, South Sudan and Yemen in particular, less so in Somalia, we in the World Food Programme have a tremendously difficult time, as does the rest of the international humanitarian community, to access the people in need.

So the big issue for us now is how can we get access, how can we improve security for these three countries? We need massive amounts of resources. I’m almost hesitant to say how much we need. For the four countries, just for food, until the end of the year, we need about 2.6 billion dollars. It’s a massive amount of money, and then our colleagues in UNICEF, in the NGO’s, all of the other organizations that are doing great work, need additional resources as well, but in fact it is something that the world can do, that the world can provide if it wants to.

So let me just summarize; I just want to say why does it matter to the U.S.? We know that in the press these days, there has been some question as to whether or not it’s worthwhile investing in these things. Why have foreign assistance? It’s just doing things over there. It’s not helping the United States. And I think that’s wrong. First of all, the United States has always been the leader in the provision of humanitarian assistance around the world. It’s something we’ve done not just since World War II but we’ve done it even before that. The United States just has it ingrained: we help people. But we also have to realize that helping people stabilizes countries. That’s what it does. It’s good for the world economy if countries are stable. When we saw the world food crisis in 2008, the world reacted because countries were being destabilized by a shortage of food. And then of course, and this is something the General will probably talk about, three of the four countries are home to global terrorism organizations. When you have countries that are destabilized, they in fact are a great environment for radicalism. So it’s something we need; there are a variety of reasons it’s important for the United States. And I’ll close by saying, I just don’t think President Eisenhower and President Kennedy were wrong when they established the World Food Programme. The reasons why they did it then are just as valid today. Thank you very much.

GENERAL WILLIAM “KIP” WARD:

Thank you Dr. Muyangwa. And I’d also like to thank Congresswomen Bass and Lee for their support for these fora and for highlighting the importance of these issues to citizens of the United States. I’m probably a strange bedfellow here with respect to being on this panel, talking about famine and food insecurity in my role as the first commander of the United States’ Africa Command. But it is precisely that role that makes my being here, if not from an expert perspective, then from a perspective of what it means to the United States of America, what it means to our national interests, and what it means to local stability.

“[W]e are in the scenario now, where on any given day, four out of six children malnourished, two out of 10 dying daily, those are examples of the inability to address such a devastating problem.”

–General William “Kip” Ward, former commander of AFRICOM

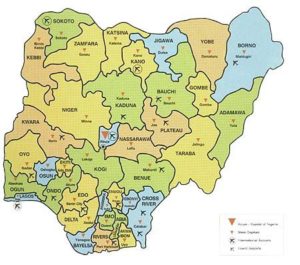

As Jon pointed out and as was mentioned in the opening remarks by Congresswoman Bass, famine, food insecurity, is probably the hugest driver to  security issues in most countries. And, as we look at Nigeria, the northeastern part of that great, great nation, up until about seven years ago, Borno could feed Nigeria. And now, we see the huge level of devastation, famine, death, caused because of what has gone on with respect to the fight against Boko Haram. as Jon pointed out, the drivers of famine can be controlled if you have an environment that allows other things to occur. The delivery of aid, infrastructure that allows the movement of persons, the ability of organizations to come in and do things that will contribute to providing a degree of stability that would otherwise not be the case. For the last seven years, northeast Nigeria has not been able to see those things occur, because of the efforts by the Nigerian government that began towards the end of the Jonathan Administration and have continued now with the Buhari Administration to address and defeat the Boko Haram that has been so devastating to northeast Nigeria. And because of the activity in that part of the nation, it not only impacts Nigeria, it impacts the entire region. And when you have the displacement of — the numbers vary, low side 2 million, up to 8 million people in various stages that have migrated to 140-plus displacement centers, with varied means of addressing the crises of 1-food, 2-water, 3-sanitation, but other drivers of instability, lack of education, I call it the lack of any hope, who are constantly being threatened by what goes on as the eradication efforts occur, or the efforts to defeat the terrorism go on, it then bodes ill for any progress to be made. So therefore, we are in the scenario now, where on any given day, and as Jon pointed out, four out of six children malnourished, two out of 10 dying daily, those are examples of the inability to address such a devastating problem. When the Nigerian armed forces mounted their sustained effort to defeat Boko Haram, going into the Zambezi Forest, disrupting the sanctuary if you will, that caused the surrounding environs in the northeast of Nigeria to then become even more threatened by the threat of the fighters of Boko Haram. You then have that coupled with the dynamic of a split within Boko Haram, where they then begin to compete with each other to see who could become the most ruthless, brutal, as they ravaged the land there in the northeast and in the surrounding areas. And the victims in all of that are the people. And so, even as there are attempts being made, and to a substantial degree, successful attempts, to stop terrorism by Boko Haram, it is creating these other effects that have absolutely devastating impacts on the people. And therein [I am here] today to address this notion of malnutrition, famine. The biggest drivers of famine — insecurity and the inability to work the land that was once theirs, and to raise crops and livestock which are the lifeblood. There are currently estimated to be 8.5 million people in Nigeria, northeast Nigeria, that require some type of assistance, and there are categories, phases that the IPC [Integrated Food Security Phase Classification–Editor] has put there, but when you get to category 3 [crisis], 4 [emergency] and 5 [famine] — 3 is severe level, and that regards 5 million people, and again, these displacement camps that are now spread in major cities, if you look at Borno [State], Maiduguri, and Aba, the two major cities, part of the problem lies in the fact that the folks who have been displaced, the internally displaced persons, don’t just go to those camps. Even with their limited mobility, they are also amongst the population, which has virtually no ability to assist in providing food and other necessary resources to help combat the conditions that exist. Lack of economic activity, inability of relief organizations to provide relief aid, inability of other organizations to promote activities that will help address the impacts of lack of water, and other things. These are the factors that have contributed to what goes on in northeast Nigeria. The root of it all is the fight against Boko Haram. And I’ll stop there.

security issues in most countries. And, as we look at Nigeria, the northeastern part of that great, great nation, up until about seven years ago, Borno could feed Nigeria. And now, we see the huge level of devastation, famine, death, caused because of what has gone on with respect to the fight against Boko Haram. as Jon pointed out, the drivers of famine can be controlled if you have an environment that allows other things to occur. The delivery of aid, infrastructure that allows the movement of persons, the ability of organizations to come in and do things that will contribute to providing a degree of stability that would otherwise not be the case. For the last seven years, northeast Nigeria has not been able to see those things occur, because of the efforts by the Nigerian government that began towards the end of the Jonathan Administration and have continued now with the Buhari Administration to address and defeat the Boko Haram that has been so devastating to northeast Nigeria. And because of the activity in that part of the nation, it not only impacts Nigeria, it impacts the entire region. And when you have the displacement of — the numbers vary, low side 2 million, up to 8 million people in various stages that have migrated to 140-plus displacement centers, with varied means of addressing the crises of 1-food, 2-water, 3-sanitation, but other drivers of instability, lack of education, I call it the lack of any hope, who are constantly being threatened by what goes on as the eradication efforts occur, or the efforts to defeat the terrorism go on, it then bodes ill for any progress to be made. So therefore, we are in the scenario now, where on any given day, and as Jon pointed out, four out of six children malnourished, two out of 10 dying daily, those are examples of the inability to address such a devastating problem. When the Nigerian armed forces mounted their sustained effort to defeat Boko Haram, going into the Zambezi Forest, disrupting the sanctuary if you will, that caused the surrounding environs in the northeast of Nigeria to then become even more threatened by the threat of the fighters of Boko Haram. You then have that coupled with the dynamic of a split within Boko Haram, where they then begin to compete with each other to see who could become the most ruthless, brutal, as they ravaged the land there in the northeast and in the surrounding areas. And the victims in all of that are the people. And so, even as there are attempts being made, and to a substantial degree, successful attempts, to stop terrorism by Boko Haram, it is creating these other effects that have absolutely devastating impacts on the people. And therein [I am here] today to address this notion of malnutrition, famine. The biggest drivers of famine — insecurity and the inability to work the land that was once theirs, and to raise crops and livestock which are the lifeblood. There are currently estimated to be 8.5 million people in Nigeria, northeast Nigeria, that require some type of assistance, and there are categories, phases that the IPC [Integrated Food Security Phase Classification–Editor] has put there, but when you get to category 3 [crisis], 4 [emergency] and 5 [famine] — 3 is severe level, and that regards 5 million people, and again, these displacement camps that are now spread in major cities, if you look at Borno [State], Maiduguri, and Aba, the two major cities, part of the problem lies in the fact that the folks who have been displaced, the internally displaced persons, don’t just go to those camps. Even with their limited mobility, they are also amongst the population, which has virtually no ability to assist in providing food and other necessary resources to help combat the conditions that exist. Lack of economic activity, inability of relief organizations to provide relief aid, inability of other organizations to promote activities that will help address the impacts of lack of water, and other things. These are the factors that have contributed to what goes on in northeast Nigeria. The root of it all is the fight against Boko Haram. And I’ll stop there.

JOHN PRENDERGAST:

Thanks to all the organizers, Congresswoman Bass, Congresswoman Lee, Congressman Meeks, for your continuing leadership on African issues. Your voices and those of your colleagues in these days are more needed than ever. What seems like the big discovery these days is that famines are man-made, as opposed to nature-driven. But this description, I think, is far too vague. It lays no accountability at the feet of which men are making these famines. And in the case of South Sudan, the most immediate cause lies in the tactics used by the senior officials in the South Sudan military and amongst the principal rebel movement in the way that they’re carrying out the current civil war. Government and rebel forces attack civilian targets much more frequently than they attack each other. They target the means of survival of civilian populations who are deemed to be unsupportive of those forces. In particular and most damaging, and this is the case in a number of places where food insecurity is raging today, they raid cattle, in areas where cows represent the inherited savings, basically the 401(k)’s, basically the means of exchange, locally. Massive cattle raids result in almost complete and utter impoverishment of entire communities, and they unleash cycles of revenge attacks that poison relations between neighbors and entire ethnic groups. The government of South Sudan has also concentrated recent attacks on areas where agricultural production traditionally fed large parts of South Sudan, not only resulting in massive human displacement, but also devastating local grain production which leads to hyper-inflation of food prices, making food inaccessible to vast swaths of the civilian population.

“What seems like the big discovery these days is that famines are man-made, as opposed to nature-driven.”

–John Prendergast, Enough Project

But destroying the means of food production is only one part of the equation that causes famine. Look, if the South Sudan government allowed humanitarian  organizations unfettered access to the survivors of these attacks, which include at this point over 3 million people who have been rendered homeless by the kinds of war tactics that have occurred, then the aid agencies would be able to prevent a famine from occurring. You wouldn’t see the 3, 4, 5 cycles hammering the people of South Sudan today. But instead, the government has obstructed access by these organizations in a number of ways, by learning some of the tactics from the Sudan government who they fought for decades, as have the rebels, thus resulting in these huge pockets of populations, including tens of thousands of children today, who have received little to no assistance at the very height of their need.

organizations unfettered access to the survivors of these attacks, which include at this point over 3 million people who have been rendered homeless by the kinds of war tactics that have occurred, then the aid agencies would be able to prevent a famine from occurring. You wouldn’t see the 3, 4, 5 cycles hammering the people of South Sudan today. But instead, the government has obstructed access by these organizations in a number of ways, by learning some of the tactics from the Sudan government who they fought for decades, as have the rebels, thus resulting in these huge pockets of populations, including tens of thousands of children today, who have received little to no assistance at the very height of their need.

And let’s be clear: if the only response to the images we’re going to be seeing with increased frequency is the humanitarian one, and the structural causes of this cycle of famine in South Sudan and other places are not addressed, then the cycle of famine will begin again next year, and the year after that. Yes, the world must do, and will do, because of the efforts of people in this room, all that it can to treat these humanitarian symptoms of the emergency, but there’s also an opportunity when there’s this kind of attention that has drawn all of you into this room this morning, to finally begin to address the root causes of some of these crises. Now in South Sudan today, the war crimes that are committed that help lead directly to famine, these war crimes actually pay. There’s no accountability for the atrocities and the looting of state resources and even of humanitarian assistance, and there’s no accountability for the famine that results from it. Billions in our taxpayer dollars have supported peacekeeping forces and humanitarian assistance already. We’ve got to keep doing that, and double down on it, in this time of need for the people of South Sudan. And one peace process after another has tried to break the cycle of violence.

“Nothing attempts to thwart the driving force of the mayhem, which in our view is the kleptocrats who have hijacked the government for their personal enrichment, and have carried out war tactics that have led directly to the famine.”

–John Prendergast, Enough Project

But nothing, unfortunately — and this is a bizarre aspect of international policy — nothing attempts to thwart the driving force of the mayhem, which in our view is the kleptocrats who have hijacked the government in Juba [Sudan’s capital city–Editor] for their personal enrichment, and have carried out war tactics that have led directly to the famine. Our new initiative — it’s called the Sentry — has conducted an investigation into the wealth accumulated by leading officials in South Sudan, who oversaw the military offensives in 2015 in Unity State that contributed directly to the current famine. We found that immediate family members of these officials are enjoying luxurious lifestyles abroad, live in lavish estates, with millions and millions of dollars moving through the international financial system in US dollars, while the situation of the civilian population in South Sudan continues to deteriorate. Essentially, we’re working on a series of follow-up reports to the one we did last September that connect the state looting directly to the famine and the ongoing conflict, and the perverse incentives that exist for these governments to commit these kinds of atrocities in order to stay in power, and without any consequence whatsoever for their actions. The looting machine, in fact, continues apace, not slowed down even by the prospect of hundreds of thousands of people starving to death. There’s been no meaningful effort to counter the networks that benefit financially and politically from conflict, from instability, from the absence of the rule of law, and even from famine. The international community needs to help make war costlier than peace, for government and rebel leaders and their international facilitators, because it isn’t just folks on the ground; there are many people in the international and financial system who are benefiting from South Sudan’s misery. Those facilitators and enablers need to be the subject of investigations as well. Choking the illicit financial flows of those folks that are responsible for this famine is the key point of leverage for giving peace an actual chance in South Sudan, because these stolen assets are the one point of vulnerability that the leading officials have. Their stolen assets are off-shored and laundered through the international financial system in us dollars. That gives the United States Treasury Department jurisdiction over crimes committed with US currency. And you see houses, you see cars, you see stuffed bank accounts, all of these manifestations of this criminal activity that is being moved through the international financial system. So I think the most promising policy approach for creating accountability in context of war and famine would combine creative Anti-Money-Laundering measures that we have honed since 9-11, combine those AML measures with targeted sanctions aimed at freezing those willing to commit mass atrocities, including those that undertook these offensives in 2015 and 2016 that led directly to famine, so you focus on freezing those leading officials out of the international financial system. That should be the objective. That would provide leverage to the international community’s efforts to bring folks to the negotiating table to create a real environment for a peace deal. A steep price needs to be paid for creating famine, and for benefiting from war.

“It’s the South Sudanese that are leading the efforts to respond to the famine. It’s the South Sudanese, courageously, who are responding to the human rights abuses. It’s the South Sudanese struggling for independent freedom of the press, freedom of association, all of the basic fundamental rights that they fought and died for, for decades, to have the newest country in the world.”

–John Prendergast, Enough Project

Even while the world responds to the famine, it’s time for us to address root causes and make those responsible pay for those crimes. And let’s be clear about this; thousands and thousands of South Sudanese — a trip we just took confirmed this to me yet again — it’s the South Sudanese that are leading the efforts to respond to the famine. It’s the South Sudanese, courageously, who are responding to the human rights abuses. It’s the South Sudanese struggling for independent freedom of the press, freedom of association, all of the basic fundamental rights that they fought and died for, for decades, to have the newest country in the world. … The US Congress can, and should, take the lead in supporting solidarity and getting resources to those folks on the ground who are struggling to turn their situation around, just as many have in other countries around Africa. the South Africans led the anti-apartheid effort, the Mozambicans rebuilt their country, the Sierra Leoneans, the Liberians, all these different countries have demonstrated that it is possible to turn things around. South Sudan is literally at its low point right now. It has hit rock-bottom. But it’s the South Sudanese who can bring it back, just like we’ve seen in other places. But it’s our role to provide solidarity and support to those efforts to turn things around. Thank you.

DR. MUNYANGWA:

Jon, do you mind saying a few words about Somalia?

JON BRAUSE:

Sure. I think Somalia is a really good country to look at because it had a famine back in 2011. It was the last, actually, sort of documented famine the world faced. And just looking over the reports, as many as 250,000 people died. And if you look at the drivers at the time, which was, of course, conflict, but there was also an associated drought in the Horn of Africa, but it was a situation where really, the war and the lack of governance made it hard for the international community to respond, so we had a situation where most of the NGO’s, most of the UN agencies couldn’t be permanently present in the country, and yet they had to plan and mobilize resources to try to get assistance to the people who needed it. Today it’s a  completely different story. While there is still Al Shabab in parts of Somalia, the government — there is a government now, and the government has the capacity to represent its people. It represents its people, it has a capital, it has security in parts of the country where there can now be a presence for the international community, so you have a situation where the government is leading the response to the crisis, and the government knows how it wants to respond and help its people. And this is just a sea change from what it was in 2011. Now I don’t want to take away from the fact that access is still hard to get in 25% of the country, or 25% of the population that need assistance, but it’s much, much different today than it was in 2011, and it’s all because, in contrast to what John was saying, when you have a government that really wants to help the people — and no government’s perfect, we all know that — but when you have a government that does want to help, and creates that environment, and leads — because it’s always the government that needs to lead — then the international community can step in behind, and provide the support that’s necessary.

completely different story. While there is still Al Shabab in parts of Somalia, the government — there is a government now, and the government has the capacity to represent its people. It represents its people, it has a capital, it has security in parts of the country where there can now be a presence for the international community, so you have a situation where the government is leading the response to the crisis, and the government knows how it wants to respond and help its people. And this is just a sea change from what it was in 2011. Now I don’t want to take away from the fact that access is still hard to get in 25% of the country, or 25% of the population that need assistance, but it’s much, much different today than it was in 2011, and it’s all because, in contrast to what John was saying, when you have a government that really wants to help the people — and no government’s perfect, we all know that — but when you have a government that does want to help, and creates that environment, and leads — because it’s always the government that needs to lead — then the international community can step in behind, and provide the support that’s necessary.

How can we prevent more people from dying?

DR. MUNYANGWA:

I think our three speakers touched on a number of issues, talking about the causes of the famine and the food insecurity in these countries, talking about root causes, talking about how conflict and insecurity have exacerbated the situation, but I think what we’re all left with from all three presentations is the sense of the scale and scope and the utter devastation that can result from this unless we come together, Africans and the international community, to address this challenge. As I listened to the numbers, the need for urgent food assistance, 5.1 million in Nigeria, 5 million in South Sudan, and 2.9 million in Somalia.

Before I get to the causes, I’d like to ask each of our speakers to reflect on the current situations in their own countries. Obviously, we need to begin the business of trying to save as many lives as possible. I cannot even begin to imagine the millions of lives that are at stake. So to each of you, as you look at South Sudan, as you look at Nigeria, and as you look at Somalia, what is the one intervention, that we could have right now, to stop the deaths from accumulating? In the very immediate instance, what can we do to prevent more people from dying and prevent famine and the current insecurity from getting any worse than it is today? So John, I’ll start with you first in South Sudan, and then I’ll come in to General Ward and then to Jon.

JOHN PRENDERGAST:

Well, I’m going to try to answer that question and pretend I’m only giving you one thing, but [that task is] too awesome. Because you have to preface it by saying that [what is needed is] a total, full-court, 120-percent global effort to provide humanitarian assistance, to demand access in all three of these African countries, and press and push. Shabab has openings now in Somalia, some would argue, to allow access that they didn’t before. The reason why 250,000 people died in Somalia in 2011 was because Shabab didn’t provide access. If there was access, they would have been able to receive assistance. There is an uncertainty now, because they’ve lost a lot, internally within Somalia, Shabab did, because of how they dealt with populations under their control, and because a lot of their fighters now are from areas that are hardest hit, so there is a familial interest at some level, so we’ve got incredible opportunities on the humanitarian front that need to be pressed and pushed.

In the context of counter-terrorism efforts in Somalia and Nigeria, one has to see that this humanitarian response is essential. If our long-term counter-terrorism efforts are going to succeed, these basic human needs need to be first and foremost. … Even if you’re solely driven by national security interests, and you’re sitting somewhere in this town, let’s try 1600 Pennsylvania [Avenue], and you just are interested in national security, there is a national security argument for providing increased humanitarian assistance in Nigeria.

“Right now, the international peace efforts, region-led, internationally-supported peace efforts in South Sudan, are largely in shambles.”

–Jon Prendergast, Enough Project

Let’s get to South Sudan, then. We’ve already said we’ve got to assert the humanitarian effort. We support that, and I would refer to Jon on specifics about how to do it. But I do believe, fundamentally, when we talk about conflict-driven famine, and then don’t have a credible international peace effort, then, what are we doing? Because, right now, the international peace efforts, region-led, internationally-supported peace efforts in South Sudan, are largely in shambles. There are all kind of competing possibilities that President [Salva] Kiir has announced, a national dialog that is completely inconclusive and controlled by the government — we’ve seen this in many places around Africa — it’s not a credible process, in the view of people who want to see an inclusive peace effort. And the IGAD [Inter-Governmental Authority on Development–Editor] process, which has been driving peace efforts since 1993 in South Sudan, in [the] north-south [conflict] and to the present, that effort has really been compromised, including some countries within IGAD saying ‘I don’t know if we should even continue because we’re so divided’. So, we need a coming-together, United Nations, African Union, IGAD, South Sudanese, on a revitalized peace effort. The situation has changed dramatically since the war began in 2013; where it was basically a bi-polar, two-party war, we now have multiple entities who have joined the fray. We don’t want to see it devolve into a Somalia-1991 sort of situation where you’ve got this internationally-resourced effort to save the elements of the peace effort that already exists that are very solid and address some of the things that are not dealt with in that peace deal.

And then I would say, to give leverage to that. Because it is meaningless to go and [try to influence] other people in the middle of a war when you have no leverage, when you cannot address their fundamental core interests. We have spent far too much energy and time diplomatically in this country, going around the world, telling people what their interests are, but then not affecting [anything]. So I would say that, if you want to create some leverage from the United States and others who care about peace in South Sudan, then you’ve got to get at what the core vulnerabilities are of these leaders. And as I’ve said, it is in the way that they are off-shoring the money that they’re looting from the fairly rich in natural resources state that South Sudan is, and then you start to go after that money, and then you start to get people’s attention. So I’m sorry, that’s a multi-layered answer, but there are solutions, that’s what I really, really want to say, and it isn’t just sending food and medicine, no one would argue that; there are multiple aspects of a comprehensive approach that could, in fact, address the core problems in all three of the countries we’re dealing with here.

GENERAL WARD:

Thanks. I probably won’t be as extensive as John was with respect to the ingredients. To be sure, to say what single thing would cause an impact, positive impact on the scenario, is very difficult. But there is something I think, and that is resources. When I say ‘resources’, there’s a plethora of resources that I’m talking about. To be sure, it includes the ‘stuff’ that the people need, and that’s an array of things, food, clean water, medicine, etc. There is a requirement that the government takes its proper role to care for its people. And in the case of Nigeria, to be sure, that’s happening today. It’s happening the way it hadn’t happened [before]. For example, when you look at what’s going on in the northeast of Nigeria as this counter-insurgency, this fight, is now being waged, you see — it may not be at the level that will solve the problem — but it’s certainly addressing the problem, because you see military units, but also some civilian organizations, supported by international relief organizations, that are addressing the problem in ways that they had not before. So, how to make the resources matter? Well, you need more of them. You talk about sovereignty. Nations have to control their borders. That’s done through security forces, some uniformed, [some] civilian, but nations have to control their borders. So that’s a component of this. And we see that being addressed in some pretty substantial ways in Nigeria. …

“There are over 180 displacement centers of various sorts, various categories, in northeast Nigeria. Less than 10 percent of them have all they need to take care of the people that are in those locations.”

–General William “Kip” Ward

You will never erase all conflict. But you have to cause conflict to be controlled such that other things can occur, other things have the ability to occur … the ability of local folks to do what makes sense for them where they live. I mentioned there are  over 180 displacement centers of various sorts, various categories, in northeast Nigeria. Less than 10 percent of them have all they need to take care of the people that are in those locations. And I talked about the fact that even many of the internally displaced persons aren’t in these centers; they are now mixed amongst the populations of the various towns, villages, etc., where they find some refuge. There’s even one location, the Capital Road, the Chinese built this road in northern Nigeria, a road that was going someplace, and I’m not certain where the road was going but it just stopped in the middle of the desert, because of the conflict. But that road had become like a rallying ground, where folks would come together. That road at least provides access for relief to occur. And so you build infrastructure, infrastructure that will allow those things that need to be delivered to be delivered, you provide an environment that is more rather than less secure, a government that is paying attention with respect to what it’s doing to care for its people. And then resources that are provided, and we all have a role in that, the international community to be sure, assets that can then allow the delivery of those resources where they’re required. And [when] all those things come together, it will help provide for a more secure environment. We all have a stake in it, including the United States of America, to increase that stability. When you look at Nigeria, you look at the most populous nation on the Continent, up until a few years ago the largest GDP on the Continent, currently, the largest population of displaced persons, so we have a stake in that, in making it happen. And so, resources is the thing. It really has multiple components.

over 180 displacement centers of various sorts, various categories, in northeast Nigeria. Less than 10 percent of them have all they need to take care of the people that are in those locations. And I talked about the fact that even many of the internally displaced persons aren’t in these centers; they are now mixed amongst the populations of the various towns, villages, etc., where they find some refuge. There’s even one location, the Capital Road, the Chinese built this road in northern Nigeria, a road that was going someplace, and I’m not certain where the road was going but it just stopped in the middle of the desert, because of the conflict. But that road had become like a rallying ground, where folks would come together. That road at least provides access for relief to occur. And so you build infrastructure, infrastructure that will allow those things that need to be delivered to be delivered, you provide an environment that is more rather than less secure, a government that is paying attention with respect to what it’s doing to care for its people. And then resources that are provided, and we all have a role in that, the international community to be sure, assets that can then allow the delivery of those resources where they’re required. And [when] all those things come together, it will help provide for a more secure environment. We all have a stake in it, including the United States of America, to increase that stability. When you look at Nigeria, you look at the most populous nation on the Continent, up until a few years ago the largest GDP on the Continent, currently, the largest population of displaced persons, so we have a stake in that, in making it happen. And so, resources is the thing. It really has multiple components.

JON BRAUSE:

Thanks. I’ll take a slightly different tack. I think, if you look at the three countries in Africa that are facing famine, and you unpack it a bit, there’s not one of those countries, absent conflict, that would ever be in this situation. So if you have to say ‘what is the number one issue’, it’s the fact that conflict is holding the countries back. South Sudan, ironically, probably of the three, it has the greatest potential, I mean, it’s just [got] unimaginable natural wealth, including agriculture. There’s no end to what could be produced in South Sudan.

“There’s not one of those countries, absent conflict, that would ever be in this situation. … the people of Africa, the people of these three countries, are already the leaders in the response. They’re not waiting.”

–Jon Brause, World Food Programme

So, it’s just the fact that the governance and therefore the conflict in those three countries needs to be constantly improved, focusing on the people, because the people of Africa, the people of these three countries, are already, as John said, the leaders in the response. They’re not waiting. They’re incredibly entrepreneurial, they’re communal, they take care of each other, but with conflict, it’s all pushed out the window. So I have to say we need to address the conflict, as John said again, the general ‘but’, I think the international community needs to stand ready to assist where and when it can. And right now, to the resource point, we don’t have that capacity. So even where we can get in, even where access is available, we are cutting rations, we are not able to fully support the people, therefore we’re not fully able to support stability. Where that little pocket of stability is, we can’t support it. So I would say let’s do work on the conflict, but the international community should try to step forward and make sure that we can help where help can take place.

Questions from the Audience (the “Q & A”)

Q: [from an Ambassador from Mali] What is expected to be done, in this time of budget cuts, for countries outside the ones discussed today but are in the Sahel region that are also enduring potential crises requiring humanitarian assistance as acknowledged by the World Food Programme as representing over 8 million people who are under threat of famine such as The Gambia, Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad and Cameroon? In Mali in particular [the questioner’s home country], conflict has displaced people inside and outside the country, and the north of Mali is generally difficult even in peacetime.

JON BRAUSE:

If I could address the Ambassador’s question, and thank you for asking because, as I mentioned at the beginning of my statement, there are 100 million people who are going to need emergency food assistance, not just 20 million in famine-stricken

Sahel Region Map from carbonbrief.org

countries, and we see a bit of donor distraction. They focus on what’s burning brightest. And of course, we have Syria in the background right now. There’s great resource drag going in certain directions. And yet, when you think about it, [there are] opportunities in places like Mali and Niger, where you have governance, where you have the opportunity to invest, and actually those donor dollars go so much farther there than they do in the famine countries. If you’re going through a famine, you’re spending huge money just to save lives. You’re not building that capacity for better development, for empowering the people, all the things you say you want, or the donor community says it wants, we’re not investing in that. And so we’re seeing a double-whammy. The resources are going to the places where they’re needed of course, to the famines, but they’re not going, there’s no significant amount of money being invested at a time when these other countries can just do such great work. So we continue to advocate for Mali, for Niger, for other countries throughout Africa, so that they’re not forgotten, but it’s a very tough battle these days.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: At this point, we were able to pose our Impudent Question. In this instance, we were somewhat pleasantly surprised that the respondents, particularly Mr. Prendergast, showed an understanding of the “root causes” he had mentioned earlier, and which had inspired the question we posed.]

Q: [from KUUMBAReport] Regarding root causes, are there enough people in positions of power who are willing to take a serious look at the real root causes from slavery, colonialism, imposition of language, religion, monetary systems and country boundaries that Africans did not choose, current resource extraction and Western-directed military incursions [such as the attack on Libya that led to the loss of the African Union’s main benefactor and freed up weapons now in the hands of Boko Haram] as causative factors in the current situation in these countries and in the Continent in general? And will enough thought be given to current solutions [African-driven and -owned food sovereignty versus Western-imposed food security] to prevent situations such as the BT cotton crisis in India, that resulted from introduction by the US and the West of genetically-modified cotton in India and that led to thousands of Indian farmer suicides, so that agriculture ‘solutions’ for Africa do not lead to similarly-disastrous outcomes?

“In the midst of famine watch the scramble for the contracts and how the ugly underbelly, again, of international investing, how that fuels violence, and you see this replicated in a number of countries around Africa, still to this day. And you see that the countries where conflict and violence is most endemic and most resistant to efforts to try to resolve those issues, at the core, I would argue, in most of those places, is unchecked greed.”

–John Prendergast, Enough Project

JOHN PRENDERGAST:

The historical context of the scramble for African resources — that we read in history books about the colonial era as if it all ended there — sort of like in this country, for some people, the perception is that, after slavery ended, what’s the problem? Not understanding Jim Crow, lynching, all the rest of it that occurred as part of the legacy. Similarly, there is a resounding legacy of that colonial era where violent, illegal extraction of Africa’s extraordinary wealth was a principal driver for the motivations of the European colonial powers. Similarly today, in a number of African countries, South Sudan is a microcosm of that, that the scramble for resources — in the case of South Sudan it’s primarily oil but the next one is gold, watch this one unfold — in the midst of famine watch the scramble for the contracts and how the ugly underbelly, again, of international investing, how that fuels violence, and you see this replicated in a number of countries around Africa, still to this day. And you see that the countries where conflict and violence is most endemic and most resistant to efforts, whether local or regional or international, efforts to try to resolve those issues, at the core, I would argue, in most of those places, is unchecked greed. It’s that confluence of corruption and violence that is driving the emergencies, and I think we can make long, academic, well-sourced assessments of that statement for all three of our countries in Africa today, the underlying rot of corruption and the use of state violence to ensure the continuation of patterns of violent extraction of resources. And the difficulty in addressing those patterns through peace processes and other approaches, counter-terrorism efforts and other things, if you’re not getting at the core issue of kleptocracy and the hijacking of state institutions so that the judicial systems are undermined, because having the rule of law would mean that the folks who are extracting those resources would actually be the ones being investigated and brought to justice. Having proper security services that protect the borders, as General Ward said, and are responsible for human security, rather in some of these countries, those are the agents of this accord or policy of extraction of resources. So, unless we address that fundamental issue, that root cause, we’re going to just keep seeing these emergencies in certain African countries. Other African countries have figured it out. They’ve worked through it. It’s not impossible. There’s good governance in many, many countries in Africa. There are lots of extraordinary, positive success stories throughout Africa, of countries overcoming that colonial legacy and turning things around, politically, economically. Works in progress all over, but dramatic, in my view. But there are a subset of countries that are still in this cycle that is very similar to what that cycle was during the colonial period. And it’s all about abject greed and the lack of any accountability for a small group of people in each of these countries who have hijacked the state institutions for their own personal benefit, with international collaborators — banks, lawyers, accountants, shipping companies, arms dealers — those are the kleptocratic networks that we’ve got to address if we want to stop these cycles from continuing.

GENERAL WARD:

I’ve been getting at the notion of those things that are sustainable, as well as those things that are done because you have a committed group of leaders that are looking at an overarching approach. The landscape, I believe, is positive. It’s not perfect but it’s positive. If I go back ten years ago, as we stood up the United States Africa Command as an example, as an example, where it was very plain and apparent that decisions that were ever made, were made as they took into account a range of things that were important for taking care of people. Including, to be sure, what was my primary focus, and I undertook that with the full understanding that that wasn’t enough in and of itself. It also required a healthy dose of what I call development, across economic sectors, across agricultural sectors, that could lead to the things that the people needed for themselves that they participated in, from manufacturing to energy, that enabled a society to sustain itself, and a commitment to it as well as an investment in it. And it also took what I used to term governance, good governance. At least governance that was more effective as opposed to less effective, taking in all of the [issues] that we’ve talked about here. From corruption to providing services in remote locations and those things. And I say that the realization of the importance of that comingling of work, I think, is increasingly recognized by leaders. People sure understand it. And if the leaders are to remain in power, then they too have to do things that reflect their understanding of it so that they can demonstrate to their people that they are in fact working on their behalf. And so, is it possible? Is there a commitment? Can it be sustainable? Yes, but only when and if you have a secure environment, more or less — won’t be perfect but more or less — when you have things being developed in a way that the people who are living there see themselves as benefiting from what’s going on in their homeland, in their area, in their geography, and governance that’s more effective rather than less effective, representing the interests of its people.

“Is it possible? Is there a commitment? Can it be sustainable? Yes, but only when and if you have a secure environment, more or less — won’t be perfect but more or less — when you have things being developed in a way that the people who are living there see themselves as benefiting from what’s going on in their homeland …”

–General William “Kip” Ward

Q: [from Dr. Malcolm Beech, president of the National Business League and the African Business League of America] How can the US encourage building capacity and capability in African businesses for in-country food processing, and how can the us HBCU’s [Historically Black Colleges and Universities] help?

JON BRAUSE:

I’m going to point you to the Feed the Future Initiative that the last Administration put so much effort into and it was really focused on doing just what you’re talking about. It’s not the response, it’s not waiting until you have a problem, it’s how do you enhance the capacity of African nations to not only produce more food but to process more food, to develop their markets. What are the key actions of each of those countries and regions where you tweak a little bit, with a little bit of resources, and actually have tremendous impact? It’s a wonderful program, and I do hope it continues.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: We noticed here that Mr. Brause made reference to Feed the Future, a program sponsored in large part by the United States Agency for International Development, USAID. While we liked the bulk of his analysis of famine in Afrika and the issues that needed to be considered, this was the one comment he made during the entire event with which we had some serious issues. The fact that he worked for 22 years at USAID, in positions of increasing responsibility and policy influence, makes the comment unsurprising, especially as he demonstrates a real concern for the people on whose behalf he speaks, and he no doubt sees the programs promoted by USAID to be on the whole, if not in total, beneficial for struggling populations around the world. Our research on the agency, while certainly leading to a similar conclusion that those working for USAID share a commitment to improving the lot of disadvantaged communities, has also, however, led us to conclude that several of its initiatives are flawed at best, and at worst, have led to disastrous consequences for a number of the communities it was designed to help, largely due to the influence of some of the same corporate opportunists Mr. Prendergast mentions in his comments.

Several years ago, when we first started attending the Africa Policy Forum events, we were introduced to the Feed the Future program and did some background research on the track record of USAID and its projects in different parts of the world. Somewhat alarmingly for us, we found that USAID had assisted in the promotion of the very BT cotton that ultimately led to the Indian farmer suicides, and the agency had run into resistance from several Latin American countries who did not want genetically-modified crops from Monsanto and other agribusiness corporations introduced in their countries. Feed the Future was reputed to be promoting Water Resistant Maize for Africa (WEMA), which was also connected to agribusiness corporations such as Cargill, Syngenta and Monsanto, as an answer to the problems of crop yields in northern Afrika, despite the assertions by food sovereignty activists that the real problem is not so much yields as it is access to the food that is available and is already being grown. Monsanto and other agribusiness corporations’ insistence on selling farmers patented, genetically-modified seeds that cannot be recycled, either by science (so-called “terminator seed technology” which has not been verified) or by law (lawsuits by agribusiness against farmers who attempted to recycle their seeds instead of buying the next generation from them), helped lead to the inability of Indian farmers to raise their crops sustainably, and, combined with the unexpectedly-high amounts of water and pesticides needed (despite industry claims to the opposite), the Indian farmers largely went bankrupt and committed suicide because they could no longer pay their debts.

Several years ago, when we first started attending the Africa Policy Forum events, we were introduced to the Feed the Future program and did some background research on the track record of USAID and its projects in different parts of the world. Somewhat alarmingly for us, we found that USAID had assisted in the promotion of the very BT cotton that ultimately led to the Indian farmer suicides, and the agency had run into resistance from several Latin American countries who did not want genetically-modified crops from Monsanto and other agribusiness corporations introduced in their countries. Feed the Future was reputed to be promoting Water Resistant Maize for Africa (WEMA), which was also connected to agribusiness corporations such as Cargill, Syngenta and Monsanto, as an answer to the problems of crop yields in northern Afrika, despite the assertions by food sovereignty activists that the real problem is not so much yields as it is access to the food that is available and is already being grown. Monsanto and other agribusiness corporations’ insistence on selling farmers patented, genetically-modified seeds that cannot be recycled, either by science (so-called “terminator seed technology” which has not been verified) or by law (lawsuits by agribusiness against farmers who attempted to recycle their seeds instead of buying the next generation from them), helped lead to the inability of Indian farmers to raise their crops sustainably, and, combined with the unexpectedly-high amounts of water and pesticides needed (despite industry claims to the opposite), the Indian farmers largely went bankrupt and committed suicide because they could no longer pay their debts.

That these same corporations were again attempting to promote patented, genetically-modified seed, this time most notably maize (corn), in Afrika through USAID’s Feed the Future Program, has raised concerns that this same pattern would repeat itself as part of the age-old Scramble for Afrika’s Resources which many Pan-Afrikan and food activists have warned about for years and to which Mr. Prendergast referred in this very Forum. Thus, we remain skeptical about the Feed the Future program and whether it will truly lead to sustainable agriculture in Afrika, controlled by Afrikans, or whether it will usher in another era of corporate control of food in the Mother Continent, which would sacrifice long-term food sovereignty with Afrikan farmer and grassroots control for short-term food security with Western and corporate control of Afrika’s food. See the links in this comment to our other articles on this issue, which in turn will link you with source articles and documents, for more information.]

Q: [from Ms. Rosemary Segero, President of Segeros International Group, which focuses on agriculture] Here we are talking about famine, the UN is talking about fighting poverty, World Bank is talking about end of poverty, and we are here talking about root of problems of famine. Why is it that the conflicts are still in Africa, as much as people are fighting to eat, we have big companies there, doing mining, making money, there are big companies there, getting oil, selling oil. Why can’t you tell these big companies, especially to General Ward — happy to see you again — how can we work on this, to make sure there is no conflict in Africa … I’m into security like you, General, we go from head of state to head of state to fight the crime-fight, conflict, before we come to famine. … The head of states, they fight [and get into conflict], so, unless we fight that, we are going to be coming here every day, to the World Bank, the UN and the Sustainable Development Goals. What can we do from here? Don’t call us next year to talk about famine. We want that answer now.

GENERAL WARD: