This week, families will gather in a festive tradition of thanksgiving. Most will sit down to a lavish dinner of turkey, collard greens and pumpkin pie with family and close friends. Some may even invoke the old Thanksgiving myths centered around the Pilgrims and their fabled encounter with the Wampanoag people (Most will not know the Indians by this name). Very few will know the full story of the encounter between the European settlers and the Indigenous community they encountered in Plymouth, Massachusetts, or the series of events that was set in motion for subsequent encounters between the White man and the Red man.

This week, families will gather in a festive tradition of thanksgiving. Most will sit down to a lavish dinner of turkey, collard greens and pumpkin pie with family and close friends. Some may even invoke the old Thanksgiving myths centered around the Pilgrims and their fabled encounter with the Wampanoag people (Most will not know the Indians by this name). Very few will know the full story of the encounter between the European settlers and the Indigenous community they encountered in Plymouth, Massachusetts, or the series of events that was set in motion for subsequent encounters between the White man and the Red man.

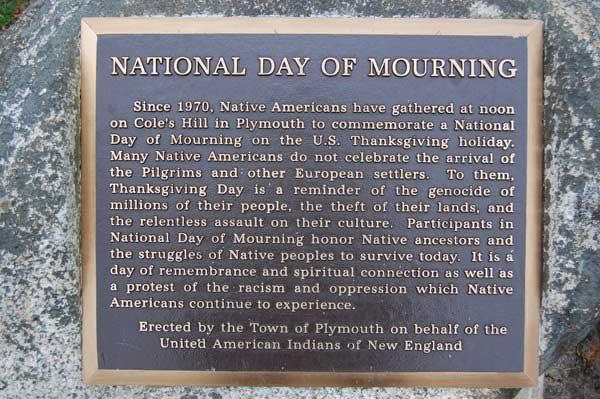

We will not be able to provide the full story here, but perhaps a few stories will help. The first one comes from the web site http://www.uaine.org/dom.htm, the online presence of the United American Indians of New England (UAINE), sponsors of an annual Day of Mourning commemoration and protest in Plymouth, Massachusetts that began in 1970. The piece was written by the primary organizers of the National Day of Mourning, Moonanum James and Mahtowin Munro.

Thanksgiving: A National Day of Mourning for Indians by Moonanum James and Mahtowin Munro

Every year since 1970, United American Indians of New England have organized the National Day of Mourning observance in Plymouth at noon on Thanksgiving Day. Every year, hundreds of Native people and our supporters from all four directions join us. Every year, including this year, Native people from throughout the Americas will speak the truth about our history and about current issues and struggles we are involved in.

Why do hundreds of people stand out in the cold rather than sit home eating turkey and watching football? Do we have something against a harvest festival?

Of course not. But Thanksgiving in this country — and in particular in Plymouth –is much more than a harvest home festival. It is a celebration of the pilgrim mythology.

According to this mythology, the pilgrims arrived, the Native people fed them and welcomed them, the Indians promptly faded into the background, and everyone lived happily ever after.

The truth is a sharp contrast to that mythology.

The pilgrims are glorified and mythologized because the circumstances of the first English-speaking colony in Jamestown were frankly too ugly (for example, they turned to cannibalism to survive) to hold up as an effective national myth. The pilgrims did not find an empty land any more than Columbus “discovered” anything. Every inch of this land is Indian land. The pilgrims (who did not even call themselves pilgrims) did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. They introduced sexism, racism, anti-lesbian and gay bigotry, jails, and the class system to these shores. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod — before they even made it to Plymouth — was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians’ winter provisions of corn and beans as they were able to carry. They were no better than any other group of Europeans when it came to their treatment of the Indigenous peoples here. And no, they did not even land at that sacred shrine called Plymouth Rock, a monument to racism and oppression which we are proud to say we buried in 1995.

The first official “Day of Thanksgiving” was proclaimed in 1637 by Governor Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of men from the Massachusetts Bay Colony who had gone to Mystic, Connecticut to participate in the massacre of over 700 Pequot women, children, and men.

About the only true thing in the whole mythology is that these pitiful European strangers would not have survived their first several years in “New England” were it not for the aid of Wampanoag people. What Native people got in return for this help was genocide, theft of our lands, and never-ending repression. We are treated either as quaint relics from the past, or are, to most people, virtually invisible.

When we dare to stand up for our rights, we are considered unreasonable. When we speak the truth about the history of the European invasion, we are often told to “go back where we came from.” Our roots are right here. They do not extend across any ocean.

National Day of Mourning began in 1970 when a Wampanoag man, Wamsutta Frank James, was asked to speak at a state dinner celebrating the 350th anniversary of the pilgrim landing. He refused to speak false words in praise of the white man for bringing civilization to us poor heathens. Native people from throughout the Americas came to Plymouth, where they mourned their forebears who had been sold into slavery, burned alive, massacred, cheated, and mistreated since the arrival of the Pilgrims in 1620.

But the commemoration of National Day of Mourning goes far beyond the circumstances of 1970.

Can we give thanks as we remember Native political prisoner Leonard Peltier, who was framed up by the FBI and has been falsely imprisoned since 1976? Despite mountains of evidence exonerating Peltier and the proven misconduct of federal prosecutors and the FBI, Peltier has been denied a new trial. Bill Clinton apparently does not feel that particular pain and has refused to grant clemency to this innocent man.

To Native people, the case of Peltier is one more ordeal in a litany of wrongdoings committed by the U.S. government against us. While the media in New England present images of the “Pequot miracle” in Connecticut, the vast majority of Native people continue to live in the most abysmal poverty.

Can we give thanks for the fact that, on many reservations, unemployment rates surpass fifty percent? Our life expectancies are much lower, our infant mortality and teen suicide rates much higher, than those of white Americans. Racist stereotypes of Native people, such as those perpetuated by the Cleveland Indians, the Atlanta Braves, and countless local and national sports teams, persist. Every single one of the more than 350 treaties that Native nations signed has been broken by the U.S. government. The bipartisan budget cuts have severely reduced educational opportunities for Native youth and the development of new housing on reservations, and have caused cause deadly cutbacks in health-care and other necessary services.

Are we to give thanks for being treated as unwelcome in our own country?

Or perhaps we are expected to give thanks for the war that is being waged by the Mexican government against Indigenous peoples there, with the military aid of the U.S. in the form of helicopters and other equipment? When the descendants of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca flee to the U.S., the descendants of the wash-ashore pilgrims term them ‘illegal aliens” and hunt them down.

We object to the “Pilgrim Progress” parade and to what goes on in Plymouth because they are making millions of tourist dollars every year from the false pilgrim mythology. That money is being made off the backs of our slaughtered indigenous ancestors.

Increasing numbers of people are seeking alternatives to such holidays as Columbus Day and Thanksgiving. They are coming to the conclusion that, if we are ever to achieve some sense of community, we must first face the truth about the history of this country and the toll that history has taken on the lives of millions of Indigenous, Black, Latino, Asian, and poor and working class white people.

The myth of Thanksgiving, served up with dollops of European superiority and manifest destiny, just does not work for many people in this country. As Malcolm X once said about the African-American experience in America, “We did not land on Plymouth Rock. Plymouth Rock landed on us.” Exactly.

[Mahtowin Munro (Lakota) and Moonanum James (Wampanoag) are co-leaders of United American Indians of New England.]

This information on the National Day of Mourning and the United American Indians of New England is available on their web site, http://www.uaine.org/dom.htm.

The 45th National Day of Mourning is to be held November 27, 2014 at 12:00 noon. The location is Coles Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

United American Indians of New England: We Are Not Vanishing. We Are Not Conquered. We Are As Strong As Ever.

Email: info@uaine.org

There is always a pot luck social following National Day of Mourning rally and march at the downstairs social hall at First Parish in Plymouth UU church on November 27.

Background Information on UAINE

Who we are: UAINE is a Native-led organization of Native people and our supporters who fight back against racism and for the freedom of Leonard Peltier and other political prisoners. We support Indigenous struggles, not only in New England but throughout the Americas.

We fight back on such issues as the racism of the Pilgrim mythology perpetuated in Plymouth and the U.S. government’s assault on poor people. We protest the use of racist team names and mascots in sports. We speak to classes in schools and universities about current issues in the Native struggle. Indigenous people from North, Central or South America who live in New England and who agree with what we are trying to do are welcome to join with us. We also welcome the support of non-Native people from the four directions. We believe very strongly that we must support others in struggle, particularly other communities of color, the lesbian and gay community, and the disabled community.

UAINE and money: UAINE is a self-supporting organization that receives no funding from any government agency. We rely on those who support us in our struggle for the funds needed to continue to fight that struggle. Any moneys we receive from our participation in any program or our speaking engagements or from any other contributions go right into the UAINE coffers. We do not have paid staffers. In other words, no one is using UAINE as a means of making a living.

UAINE and the history of National Day of Mourning: In 1970, United American Indians of New England declared US Thanksgiving Day a National Day of Mourning. This came about as a result of the suppression of the truth. Wamsutta, an Aquinnah Wampanoag man, had been asked to speak at a fancy Commonwealth of Massachusetts banquet celebrating the 350th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims. He agreed. The organizers of the dinner, using as a pretext the need to prepare a press release, asked for a copy of the speech he planned to deliver. He agreed. Within days Wamsutta was told by a representative of the Department of Commerce and Development that he would not be allowed to give the speech. The reason given was due to the fact that, “…the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place.” What they were really saying was that in this society, the truth is out of place.

What was it about the speech that got those officials so upset? Wamsutta used as a basis for his remarks one of their own history books – a Pilgrim’s account of their first year on Indian land. The book tells of the opening of my ancestor’s graves, taking our wheat and bean supplies, and of the selling of my ancestors as slaves for 220 shillings each. Wamsutta was going to tell the truth, but the truth was out of place.

Here is the truth: The reason they talk about the pilgrims and not an earlier English-speaking colony, Jamestown, is that in Jamestown the circumstances were way too ugly to hold up as an effective national myth. For example, the white settlers in Jamestown turned to cannibalism to survive. Not a very nice story to tell the kids in school. The pilgrims did not find an empty land any more than Columbus “discovered” anything. Every inch of this land is Indian land. The pilgrims (who did not even call themselves pilgrims) did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. They introduced sexism, racism, anti-lesbian and gay bigotry, jails, and the class system to these shores. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod — before they even made it to Plymouth — was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians’ winter provisions as they were able to carry. They were no better than any other group of Europeans when it came to their treatment of the Indigenous peoples here. And no, they did not even land at that sacred shrine down the hill called Plymouth Rock, a monument to racism and oppression which we are proud to say we buried in 1995.

The first official “Day of Thanksgiving” was proclaimed in 1637 by Governor Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of men from Massachusetts who had gone to Mystic, Connecticut to participate in the massacre of over 700 Pequot women, children, and men.

About the only true thing in the whole mythology is that these pitiful European strangers would not have survived their first several years in “New England” were it not for the aid of Wampanoag people. What Native people got in return for this help was genocide, theft of our lands, and never-ending repression.

But back in 1970, the organizers of the fancy state dinner told Wamsutta he could not speak that truth. They would let him speak only if he agreed to deliver a speech that they would provide. Wamsutta refused to have words put into his mouth. Instead of speaking at the dinner, he and many hundreds of other Native people and our supporters from throughout the Americas gathered in Plymouth and observed the first National Day of Mourning. United American Indians of New England have returned to Plymouth every year since to demonstrate against the Pilgrim mythology.

On that first Day of Mourning back in 1970, Plymouth Rock was buried not once, but twice. The Mayflower was boarded and the Union Jack was torn from the mast and replaced with the flag that had flown over liberated Alcatraz Island. The roots of National Day of Mourning have always been firmly embedded in the soil of militant protest.

- For More Information Contact United American Indians of New England/LPSG

- Phone: (617) 286-6574

E-mail: info@uaine.org

Website: http://www.uaine.org

Frank B. (Wamsutta) James 1923-2001

The man who sparked the National Day of Mourning protest and march was known  as Wamsutta Frank James. The following short bio is taken from his obituary, written upon his death in 2001, and posted on http://www.nativeweb.org/obituaries/wamsutta.html.

as Wamsutta Frank James. The following short bio is taken from his obituary, written upon his death in 2001, and posted on http://www.nativeweb.org/obituaries/wamsutta.html.

Frank B. (Wamsutta) James, an Aquinnah Wampanoag elder and Native American activist, died February 20, 2001 at the age of 77. James first came to national attention in 1970 when he, with hundreds of other Native Americans and their supporters, went to Plymouth and declared Thanksgiving day a National Day of Mourning for Native Americans. The National Day of Mourning protest in Plymouth continues to this day, now led by his son.

James was proud of his Native American heritage long before it was fashionable to do so, and spent many hours researching the history of the Wampanoag Nation and of the English invasion of the New England region.

A brilliant trumpet player, James was the first Native American graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music in 1948. While many of his classmates secured positions with top symphony orchestras, James was flatly told that, due to segregation and racism, no orchestra in the country would hire him because of his dark skin. While at the Conservatory, he became the first non-white member of the Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia fraternity. In 1957, James became a music teacher on Cape Cod, where he was a very popular and influential instructor. He went on to become the Director of Music of the Nauset Regional Schools, retiring in 1989.

James devoted much of his life to fighting against racism and to fighting for the rights of all Indian people. James often traveled long distances to be at Native American protests, including the Trail of Broken Treaties in Washington, DC in 1972, when Native American activists took over the Burea of Indian Affairs building, and the historic Longest Walk from California to Washington, DC in 1978.

Although he was less active in recent years due to declining health, he always maintained an interest in all Native American issues. He was the moderator of United American Indians of New England from 1970 until the mid-1990s. [UAINE is the organization which organizes the National Day of Mourning protests in Plymouth.]

A former President of the Federated Eastern Indian League, he was also the Executive Director of Operation Mainstream on Cape Cod in the 1970s. [FEIL was an organization of all Native American people from the East Coast.] [Operation Mainstream was a federally-funded job retraining program serving the Cape and Islands; it was later absorbed by CETA.]

In the 1970s, he was appointed by Gov. Sargent to the newly-created Massachusetts Commission on Indian Affairs. James later resigned from the Commission due to what he felt was the state’s refusal to take Native American needs and issues seriously.

James was considered by many who knew him to be a true Renaissance man. In addition to his many other talents, he was also a gifted painter, scrimshaw artist, silversmith, draftsman, builder, raconteur, model shipmaker, fisherman, and sailor.

He is survived by his sisters, his children and his grandchildren.

Below, from UAINE’s web site at http://www.uaine.org/wmsuta.htm, is the suppressed speech of Wamsutta Frank James, the speech he was supposed to have delivered on Thanksgiving Day, 1970, the day the National Day of Mourning protest began.

THE SUPPRESSED SPEECH OF WAMSUTTA (FRANK B.) JAMES, WAMPANOAG

To have been delivered at Plymouth, Massachusetts, 1970

ABOUT THE DOCUMENT: Three hundred fifty years after the Pilgrims began their invasion of the land of the Wampanoag, their “American” descendants planned an anniversary celebration. Still clinging to the white schoolbook myth of friendly relations between their forefathers and the Wampanoag, the anniversary planners thought it would be nice to have an Indian make an appreciative and complimentary speech at their state dinner. Frank James was asked to speak at the celebration. He accepted. The planners, however, asked to see his speech in advance of the occasion, and it turned out that Frank James’ views — based on history rather than mythology — were not what the Pilgrims’ descendants wanted to hear. Frank James refused to deliver a speech written by a public relations person. Frank James did not speak at the anniversary celebration. If he had spoken, this is what he would have said:

I speak to you as a man — a Wampanoag Man. I am a proud man, proud of my  ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction (“You must succeed – your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!”). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first – but we are termed “good citizens.” Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so.

ancestry, my accomplishments won by a strict parental direction (“You must succeed – your face is a different color in this small Cape Cod community!”). I am a product of poverty and discrimination from these two social and economic diseases. I, and my brothers and sisters, have painfully overcome, and to some extent we have earned the respect of our community. We are Indians first – but we are termed “good citizens.” Sometimes we are arrogant but only because society has pressured us to be so.

It is with mixed emotion that I stand here to share my thoughts. This is a time of celebration for you – celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People.

Even before the Pilgrims landed it was common practice for explorers to capture Indians, take them to Europe and sell them as slaves for 220 shillings apiece. The Pilgrims had hardly explored the shores of Cape Cod for four days before they had robbed the graves of my ancestors and stolen their corn and beans. Mourt’s Relation describes a searching party of sixteen men. Mourt goes on to say that this party took as much of the Indians’ winter provisions as they were able to carry.

Massasoit, the great Sachem of the Wampanoag, knew these facts, yet he and his People welcomed and befriended the settlers of the Plymouth Plantation. Perhaps he did this because his Tribe had been depleted by an epidemic. Or his knowledge of the harsh oncoming winter was the reason for his peaceful acceptance of these acts. This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people.

What happened in those short 50 years? What has happened in the last 300 years? History gives us facts and there were atrocities; there were broken promises – and most of these centered around land ownership. Among ourselves we understood that there were boundaries, but never before had we had to deal with fences and stone walls. But the white man had a need to prove his worth by the amount of land that he owned. Only ten years later, when the Puritans came, they treated the Wampanoag with even less kindness in converting the souls of the so-called “savages.” Although the Puritans were harsh to members of their own society, the Indian was pressed between stone slabs and hanged as quickly as any other “witch.”

And so down through the years there is record after record of Indian lands taken and, in token, reservations set up for him upon which to live. The Indian, having been stripped of his power, could only stand by and watch while the white man took his land and used it for his personal gain. This the Indian could not understand; for to him, land was survival, to farm, to hunt, to be enjoyed. It was not to be abused. We see incident after incident, where the white man sought to tame the “savage” and convert him to the Christian ways of life. The early Pilgrim settlers led the Indian to believe that if he did not behave, they would dig up the ground and unleash the great epidemic again.

The white man used the Indian’s nautical skills and abilities. They let him be only a seaman — but never a captain. Time and time again, in the white man’s society, we Indians have been termed “low man on the totem pole.”

Has the Wampanoag really disappeared? There is still an aura of mystery. We know there was an epidemic that took many Indian lives – some Wampanoags moved west and joined the Cherokee and Cheyenne. They were forced to move. Some even went north to Canada! Many Wampanoag put aside their Indian heritage and accepted the white man’s way for their own survival. There are some Wampanoag who do not wish it known they are Indian for social or economic reasons.

What happened to those Wampanoags who chose to remain and live among the early settlers? What kind of existence did they live as “civilized” people? True, living was not as complex as life today, but they dealt with the confusion and the change. Honesty, trust, concern, pride, and politics wove themselves in and out of their [the Wampanoags’] daily living. Hence, he was termed crafty, cunning, rapacious, and dirty.

History wants us to believe that the Indian was a savage, illiterate, uncivilized animal. A history that was written by an organized, disciplined people, to expose us as an unorganized and undisciplined entity. Two distinctly different cultures met. One thought they must control life; the other believed life was to be enjoyed, because nature decreed it. Let us remember, the Indian is and was just as human as the white man. The Indian feels pain, gets hurt, and becomes defensive, has dreams, bears tragedy and failure, suffers from loneliness, needs to cry as well as laugh. He, too, is often misunderstood.

The white man in the presence of the Indian is still mystified by his uncanny ability to make him feel uncomfortable. This may be the image the white man has created of the Indian; his “savageness” has boomeranged and isn’t a mystery; it is fear; fear of the Indian’s temperament!

High on a hill, overlooking the famed Plymouth Rock, stands the statue of our great Sachem, Massasoit. Massasoit has stood there many years in silence. We the descendants of this great Sachem have been a silent people. The necessity of making a living in this materialistic society of the white man caused us to be silent. Today, I and many of my people are choosing to face the truth. We ARE Indians!

Although time has drained our culture, and our language is almost extinct, we the Wampanoags still walk the lands of Massachusetts. We may be fragmented, we may be confused. Many years have passed since we have been a people together. Our lands were invaded. We fought as hard to keep our land as you the whites did to take our land away from us. We were conquered, we became the American prisoners of war in many cases, and wards of the United States Government, until only recently.

Our spirit refuses to die. Yesterday we walked the woodland paths and sandy trails. Today we must walk the macadam highways and roads. We are uniting We’re standing not in our wigwams but in your concrete tent. We stand tall and proud, and before too many moons pass we’ll right the wrongs we have allowed to happen to us.

We forfeited our country. Our lands have fallen into the hands of the aggressor. We have allowed the white man to keep us on our knees. What has happened cannot be changed, but today we must work towards a more humane America, a more Indian America, where men and nature once again are important; where the Indian values of honor, truth, and brotherhood prevail.

You the white man are celebrating an anniversary. We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian.

There are some factors concerning the Wampanoags and other Indians across this vast nation. We now have 350 years of experience living amongst the white man. We can now speak his language. We can now think as a white man thinks. We can now compete with him for the top jobs. We’re being heard; we are now being listened to. The important point is that along with these necessities of everyday living, we still have the spirit, we still have the unique culture, we still have the will and, most important of all, the determination to remain as Indians. We are determined, and our presence here this evening is living testimony that this is only the beginning of the American Indian, particularly the Wampanoag, to regain the position in this country that is rightfully ours.

Wamsutta

September 10, 1970

(Right) HOMELAND SECURITY POSTER, SIERRA MADRE MOUNTAINS, MEXICO: Geronimo pictured with braves, photographed before surrender to General Crook, March 27, 1886 (photo by C.S. Fly).

(Right) HOMELAND SECURITY POSTER, SIERRA MADRE MOUNTAINS, MEXICO: Geronimo pictured with braves, photographed before surrender to General Crook, March 27, 1886 (photo by C.S. Fly).

APACHE WARRIORS: (l-r) Yanozha, Chappo (Geronimo’s son), Fun (Yanozha’s half brother), Geronimo.

From the web sites http://www.californiaindianeducation.org/indian_warriors/geronimo.html and www.callie.org