The consensus of the group was sincere, definitive and straightforward. There were at least five of us, all but myself being Afrikans who had immigrated to the United States from Nigeria. I would be considered either as a member of the “Old Diaspora” (people of Afrikan descent due to the enslavement of our Ancestors during the Transatlantic Slave Trade or Maafa, with Afrikan immigrants being the “New Diaspora”), or simply as a member of the “Afrikan Diaspora”, with immigrants from Afrika being considered “Continental Afrikans”. Everyone on the conference call was agreed, including myself, about one critical issue facing the Afrikan Continent, though my personal knowledge of the topic at hand was limited at best.

“We must do something to end corruption in Afrika.”

If you read the various reports from the international organizations that claim to care about Afrikan people, you will see this refrain repeated as if it were a sacred mantra: If Afrika is to raise herself out of the toxic soup of suffering in which her people are mired, her leaders must find a way to weed out the corruption that infests the Mother Continent like an epidemic. When “corruption” is thought to be too strong a word, politicians, diplomats and writers reach for its warmer-sounding feel-good handy-dandy substitute: “good governance.” Unfortunately, this term “good governance” too often is taken to imply a more Western style of governance, usually akin to the United States’ version of “democracy”, while rejecting outright systems such as Socialism and Communism or more indigenous Afrikan Consensus-based models of communal governing.

This analysis seems consistent throughout the continent of Afrika. Heads of state, from Cote D’Ivoire’s Laurent Bagbo to Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe, “holding on to power” for three and four decades as though the presidency of their countries were their own personal property. The “Arab Spring” that swept across North Afrika last year seemed partly motivated by the desire of such heads of state as Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak and Libya’s “Brother Leader” Muammar Gaddafi to stay in office by all means possible, including, according to their detractors, the repression of political dissent. It must be stated, however, that there seemed to be a primarily NATO-led incentive to eliminate President Gaddafi, just as the assault itself would not have succeeded had it not been for a great deal of NATO duplicity about “protecting civilians” and NATO bombing of Tripoli and Sirte. Cote D’Ivoire’s Bagbo has since been unseated, and the warning bells are ringing for other long-entrenched Afrikan leaders.

Of course, the emergence of the so-called “Big Men” in Afrika became well-known immediately after Afrikan nations began to assert their independence in the 1960’s with the founding of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor to the modern-day African Union (AU). The primary colonial powers, France, Britain, Portugal and Belgium, found their grip on the Continent loosening, and as the OAU was working to break these colonial bonds, looking upon Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and Patrice Lumumba of the Congo as shining examples of Afrikan liberation, the colonial powers saw the need to destabilize and put out these shining lights as quickly as possible.

Pillage of the Mother Continent

Thus began the destabilization campaigns: the assassination of Lumumba, the encirclement of Nkrumah and the prosecution of Kenyatta (who was defended by The Honorable Dudley Thompson during the Mau Mau trials — see accompanying article). In particular with Lumumba and the Congo, the destabilization campaign worked like a charm: Colonel Joseph Mobutu, who had taken Lumumba prisoner, tortured and murdered him, became the president of the new Zaire and, during a 30-year reign of terror, proceeded to rob the country of tens of millions of dollars while allowing US-based multinational corporations to strip the country first of its rich rubber, then its gold and other gems, leading to its current situation as the world’s primary source of coltan (for cell phones). A similar military coup and dictatorship in Nigeria by General Ibrahim Babangida and General Sani Abacha has helped bring us to the current state in the Niger River Delta: major oil companies such as Chevron and Royal Dutch Shell drill for oil while mobile units of “police thugs” known as the Kill-and-Go wreak havoc and spread terror among any who would resist the rapacious practices of Big Oil, even after the “democratically-elected” regimes of Presidents Olusegun Obasanjo, Imaru Yar’Adua and Goodluck Jonathan. And while Ethiopia holds the distinction of never having been conquered and colonized as the other states had been, its current situation, long after H.I.M. Selassie’s transition to the Ancestors, is far from that nation’s glory days: President Meles Zenawi having been coerced by the US to launch an invasion of neighboring Somalia to stop the reputed spread of Islamist rule there, and disease and famine spreading throughout the region.

Meanwhile, all across the countries of Northern and even Central Afrika, the battle rages on between the Islamic, self-proclaimed “Arab” north and the mostly-Christian south, with those who still practice their indigenous spirituality (Akan, Yoruba, Vodou, etc.) are caught in the middle.

Certainly, the African Union and its member states are working to eliminate corruption through efforts to introduce political reforms, but what are their examples and who are their guides? A string of Western monarchies and so-called “democracies” that have their own sordid histories of corruption and oppression, most notably directed against the very Afrikan nations they now seek to advise? The same nations that currently face an economic disaster as well as a growing grassroots rebellion in the form of the Occupy movement?

But this issue is clearly not the only problem facing the Mother Continent. Even though the popular image of Afrika as a backward “dark continent” is little more than a stereotype to the informed observer, the fact remains that there is much poverty there. Our problem is often that we lack the proper information to see and understand the links between the poverty and instability on the Continent and their underlying causes.

The poverty on the Continent can be traced to a number of factors, including climate (desertification in North Afrika was considered one of the underlying causes of the Darfur conflict), the continuing influence of the “former” colonial powers in Afrika’s economy (such as the French government’s imposition of the CFA Franc on the Francophone countries, the use of the British Pound in Kenya and the prominence of the dollar in other Afrikan nations, all of which are used to siphon off Afrikan wealth to French, British and US banks) and the rapacious practices of the extractive industries on the Continent (such as gold, diamonds and other precious gems in Western and Southern Afrika, oil in the Niger River Delta and Libya, and coltan in DR Congo).

These rapacious practices bring us to another major issue impacting Afrika: environmental destruction. The same extractive industries that are making a killing, figuratively and literally, on the Continent are also destroying its land, water and air. Thus, the Nigerian military junta under Abacha arrested, tried, convicted and executed Ogoni environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight others in 1995 while officials of Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell and the United States simply stood by and watched. Thus the continuing diamond mines in South Africa and the practice of sending children up into the mountains of DR Congo to dig for tantalum powder to produce the coltan we all use in our cell phones, DVD players and computers.

Central and South America

The country in the Western Hemisphere with the largest number of people of Afrikan descent is — no, not the United States — Brazil, with an estimated 85 to 115 million Afrodescendants. But, as Professor Leonard Jeffries once stated, “they have been given 55 different ways to describe themselves other than Black.” Thus, a major part of the problem there is one of identity. It becomes difficult to speak to someone about Pan-Afrikanism, or even discrimination and racism, if they refuse, or fail, to realize their own heritage and the fact that there are those who will seek to exploit them for it. As a result, they may not realize where the violence of military takeovers, the destruction of resource extraction or the scourge of drugs come from; only that a series of crooked rulers seem to come to power as multinational corporations make larger and larger fortunes at the expense of the people.

Fortunately, there are those who are working to reverse this situation. Because the primary language in Brazil is Portuguese, the language barrier has made organizing difficult, but there are groups inside Brazil that are working to educate their people. There has been somewhat more progress in Central America, where the Organización Negra Centroamericana (ONECA), or the Central American Black Organization (CABO) has established a means to speak on behalf of Afrodescendant populations in seven of the eight Central American countries.

South America has suffered, as a whole, from many of the same abuses that have been heaped upon Afrika, especially with the discovery of natural resources that can be exploited. Chilean president Salvador Allende was assassinated on September 11, 1973 in large measure to open up Chile’s copper reserves for extraction by US-based multinational corporations. Other countries, from Argentina to Brazil to Colombia to Venezuela, have been targeted for their resources, and where a non-compliant government prevented the multinational corporations from claiming their prize, that government had to be removed and those who supported it needed to be eliminated (at least two attempted coups d’etat against Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez have been traced to planners in the United States). The tool of choice, invariably, was the reign of terror, and the bringers of this terror were right-wing death squads. Tens of thousands across the continent were arrested, killed or “disappeared”. Many of these were Indigenous descendants of the Maya, but this method was used to devastating effect, particularly against Afrodesdcendants, in the Caribbean.

The Caribbean: Independence Will Be Punished

The island nations of Jamaica and The Bahamas are very popular as tourist attractions, essentially treated as “America’s Caribbean playgrounds” by vacationers who focus on the crystal-clear water, the music and the parties without giving a second thought to the situations in the “poorer areas” of these countries, primarily because resort operators do not show these areas to visitors so as not to ruin their vacations or the companies’ bottom lines. These island nations have managed to maintain a level of stability because they remain part of the British Empire, much like those that are considered possessions or territories of the United States and France.

The one island nation in the Caribbean that stands out in this regard is the one that earned its independence by force of arms in 1804. Haiti (which, according to activists I’ve met, is actually an adulteration of the original Taino name Ayiti, which means “Land of Mountains”) established itself as the Western Hemisphere’s first independent Black nation after the revolution led by Dutty Baukman, Toussaint L’Overture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines ejected first the Spanish and then the French colonial regimes there. However, the French, aided by the United States and Canada, instituted a blockade of the island and forced Ayiti’s young government to pay tens of millions of dollars to lift the blockade and earn world recognition. Since then, a series of coups and dictatorships sponsored by the United States (specifically, those of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier from 1957 – 1971, his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier from 1971 – 1986, and Raoul Cedras after the 1991 overthrow of elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide) and the imposition of “neoliberal” market-driven policies of privatization have taken the people of Ayiti to the brink of total collapse. The continued presence of elements of the old Duvalier regimes, specifically the tonton macoute death squads, the mistreatment of Ayiti’s poor by a number of UN-led “security forces”, and the US’s refusal to tolerate the return of president Aristide after yet another US-sponsored coup in 2004, have worked to prevent Ayiti and its people from recovering. Then, as though to bolster the opinion of some that Ayiti’s people “turned against God” when the revolution was launched with a Vodou ceremony, the massive earthquake in January 2010 and several hurricanes that followed have caused the nation to spiral to its most desperate state in recent memory.

The United States: Hardly One to Talk

Meanwhile, despite a higher average standard of living in the United States, there seems to be a much wider variety of ills that face Afrikan people. Perhaps this is because in the West, there is greater access to the mass media, which is always in search of the next scandal to help jump-start magazine sales or increase viewership. Of course, the issues discussed in the major media bear little resemblance to those recognized by community activists and Pan-Afrikanists: while the major media concentrate on issues of poverty, education, drugs, crime and the “moral deficit” of specific underprivileged communities, the activists often point to their mirror-images: income inequality that leads to poverty, the “benign neglect” of the social safety net which impoverishes the public schools, desperate poverty which pushes communities toward criminality to survive and drug abuse to escape their misery, the targeting of communities of color (primarily Afrikan and Latino) for disproportionate harassment, brutality, arrest and prosecution, and the rampant hypocrisy of a regime that oppresses the poor and politically targets activists while giving financial “incentives” to the rich.

Specific examples bring these issues to life: bailouts for banks and other corporations which, in turn, foreclose on struggling homeowners who were misled into predatory housing loans. Local and national budgets that de-fund schools, libraries and recreation centers for the youth while earmarking money for the building of ever more prisons, including “youth jails”, while militarizing police and increasing the US military arsenal. The article in the San Jose-Mercury News by reporter Gary Webb in the 1980’s that showed the CIA had helped arrange the flooding of South Central Los Angeles with cocaine to fund right-wing military death squads in South America while criminalizing the nation’s youth and providing fodder for the infamous “war on drugs”. The cases of Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, Oscar Grant and Adolph Grimes that highlight the continuing brutalization of Black (and Latino) males by police. The disproportionate numbers of people of Afrikan descent incarcerated, despite conflicting national crime statistics. The continuing cases of those who were targeted for their political beliefs, such as former Black Panthers Marshall “Eddie” Conway, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Sundiata Acoli, Jalil Muntaqim, Mutulu Shakur, Ed Poindexter, Veronza Bowers and Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa, American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier and the MOVE Nine (see story elsewhere in this issue). The executions of Shaka Sankofa in 2000 and Troy Davis in 2011, among others, whose guilt was not even supported by the evidence. All of this occurring against a backdrop of historic and continuing racism from employment discrimination to policies leading to Black land loss (for example, with the Black Farmers in North Carolina and Black communities in nearby Nova Scotia, Canada) to the occasional, but glaring, wink-and-nod, look-the-other-way response to instances of White vigilante lynch-mob violence. This situation is not made easier by the fact that many (though far from all) Afrodescendants in the United States see themselves purely as Americans and feel no connection whatsoever to the Continent of their Ancestors, and even some immigrants direct from Afrika seem detached from the events and issues back home, as though by immigrating to the United States they have somehow escaped from Global White Supremacy. Not much different from our Brothers and Sisters in Brazil, we have much work to do in opening the minds of Afrikan people living in the United States.

Meanwhile, issues that endanger the entire populace, Black and White, range from political policing (such as the response to the recent “Occupy” protests) and the destruction of the environment in the form of the Deepwater Horizon explosion in 2009, the Exxon Valdez disaster in 1989, mountaintop removal in West Virginia, the continuing struggles of the people in the Gulf Region and the Keystone XL Pipeline, which is still being touted by right-wing interests in an effort to exploit the Canadian tar sands, perhaps the dirtiest energy project in the world today. It is only a matter of time until the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan is forgotten and the US sends the entire planet hurtling headlong, once again, toward potential nuclear catastrophe. At the same time, the threat of war seems to be getting only worse, with saber-rattling toward Iran, the recent NATO-led war in Libya and the US’s constant search for a host country on the Mother Continent for AFRICOM, the latest attempt to militarize Afrika for the purposes of the West. All the while, the bottom lines of the major corporations continue to spiral upward, the difference between the rich and the poor grows ever greater, and the populace in general grows more and more cynical and alienated from the entire “democratic” political process.

The Science of Alienation

At the 2009 National Conference of the Sixth Region Diaspora Caucus (for which I am the Maryland State Facilitator), we had the honor of meeting a number of truly insightful people from across the Afrikan World.

Baba Prosper Ndabishuriye is from Burundi. He told us about how Belgium and United States had successfully divided the people of Burundi and Rwanda by elevating the Tutsi above the Hutu in importance and then systematically mistreating the Hutu. This helped set the stage for the 100-day Rwandan genocide of 1994. The actual catalyst was the murder of Hutu Presidents Juvénal Habyarimana of Rwanda and Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi on April 6, 1994 when the airplane carrying them was shot down as it prepared to land in Kigali, killing everyone on board. Though the missile was later traced to Hutu rebels and not Tutsis, these divisions and the assassination of the President led to a rampage against Rwanda’s Tutsis and Hutu political moderates on April 7, 1994. Many of the rifts created before and during that horrific event in history remain today between the Hutu and the Tutsi, though many like Baba Prosper are working every day to bring healing to these countries.

We also heard from a Brother from Sudan, who had immigrated to the United States several years before. He related to us his story of woe: he had arrived in the Seattle area and was immediately greeted as a new immigrant by US officials who told him to “stay away from the Afrikan-Americans; they hate Afrikans and will only hurt you.” And he followed that advice faithfully, avoiding all contact with members of the “Old Diaspora”, until the day he was accosted, beaten and arrested by a policeman. As he sat in a jail cell, with no one to come to his aid, his plight was related to an Afrikan-American Sister in Seattle who was also a member of SRDC. She was the only one who came to help him, putting up his bail and arranging for his defense on the trumped-up charges against him. As he told us this story, all of us in the room reached out to him and welcomed him into the fold of conscious Pan-Afrikan activists. I have not heard from him since that day, but my hope is that he has been able to maintain his faith in Pan-Afrikan unity and has not been once again turned against his own people by those who truly would abuse him and all of us.

On a broader scale, we see Afrikans from the Continent, Afrikans in the Caribbean, Afrikans in South America, Afrikans in Europe and Afrikans in the United States all divided against each other by the propaganda machines set in place by their historic oppressors. They have elevated the process of alienation to a science and applied it against Afrikan people around the globe.

So, What Does All This Tell Us?

Let’s back away from the picture for a minute. One is reminded of the tale of the three blind men who are asked to identify an object through touch. One feels a large, rough, rounded surface and concludes the object is a rock. Another touches something thick, hard, vertical and cylindrical and pronounces the object to be a tree. The third examines a long, leathery, undulating object and declares it is a snake. It is not until they compare notes that they realize that they were all touching different parts of an elephant.

One can see a similar situation in the world today. In one part of the world, we see poverty, drugs and crime. In another, we see political corruption, military repression and mass starvation. In yet another, it’s an impoverished population on the brink of environmental catastrophe. The reason why we seem unable to effectively deal with these various crises is we insist that these situations are unrelated.

In the United States, when a police officer guns down yet another unarmed Black youth, the Fraternal Order of Police is quick to label such an occurrence an “isolated incident”. The general public seems to accept this explanation and continues on in a condition of blissful ignorance, but veteran community activists are well aware that not only is police brutality a widespread problem within American society, but it is also indicative of a pervasive “us versus them” mentality that can be found in almost every urban police force. We can learn from the tale of the blind men and the elephant, and the real-life example of police brutality gives us a real-world example of how we must see the problems of the world, especially as they impact upon people of Afrikan descent around the globe.

This analysis may seem to some to be the idle ravings of a madman, but this writer sees Afrikan communities around the world wrestling with what they believe are a bunch of snakes, each acting independently. In Afrika, people are struggling with the vipers of “corruption”, “tribalism” and “militarism”. In Central and South America, we are fighting the serpents of “drugs”, “militarism” and “inequality” with a dose of identity crisis thrown in. In the Caribbean, we either accept the pythonic embrace of the colonial powers or we feel the poisonous fangs of “dictatorship”, “impoverishment” and exposure to catastrophe. And in the United States, we are subjected to the lethal bites of “police brutality”, “political imprisonment”, “economic inequality”, “legal and illegal lynching” and “systemic institutional racism”. Meanwhile, we are all told that we are superior to other Children of Afrika, we really have no connection whatsoever to them or to our ancestral home, that they are in many cases responsible for our predicament and that we must in fact join with our historic oppressors against our Brothers and Sisters in other parts of the world.

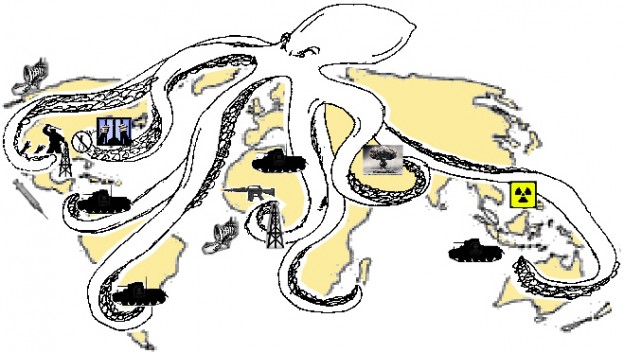

We are not dealing with “isolated incidents” here. What we are wrestling with are not a variety of snakes, even though it may seem as though we are all caught in a pit of vipers. What we are fighting is not several beasts but one. Not multiple snakes, but in each case, one tentacle of a giant octopus, an octopus of Global White Supremacy, a doctrine that seeks to overrun Indigenous civilizations around the world, be they in Afrika, in Australia, in the Americas or even, when things become sufficiently desperate, the less-fortunate or more-aware White populations in the world.

We must realize that this is a single beast that is executing a single, coordinated plan of dominance around the world. And we must fight against it in a coordinated, unified way. We must learn to overcome the thinking that has separated us for so many decades, so many centuries. Afrikans from the Americas, from Europe, from Asia, from the Island Nations and from the Mother Continent must unite if we are to throw off the chains of oppression and exploitation once and for all.

If I had to describe this short article in 1 word, it would be awesome. I think this is a fantastic piece of work that deserves recognition. I enjoyed reading it. I completely agree with you.

Its like you study my ideas! You appear to grasp a lot approximately this, like you wrote the e guide in it or something. I believe that you just could do with some p.c. to power the message house a little, but other than that, that’s magnificent blog. An excellent study. I’ll certainly be back.

Everything is very open getting a precise clarification of the issues. It was certainly informative. Your internet site is extremely helpful. Thanks for sharing!

I truly value this post. I’ve been looking throughout for this! Thank goodness I discovered it on Bing. You have made my day! Thank you again